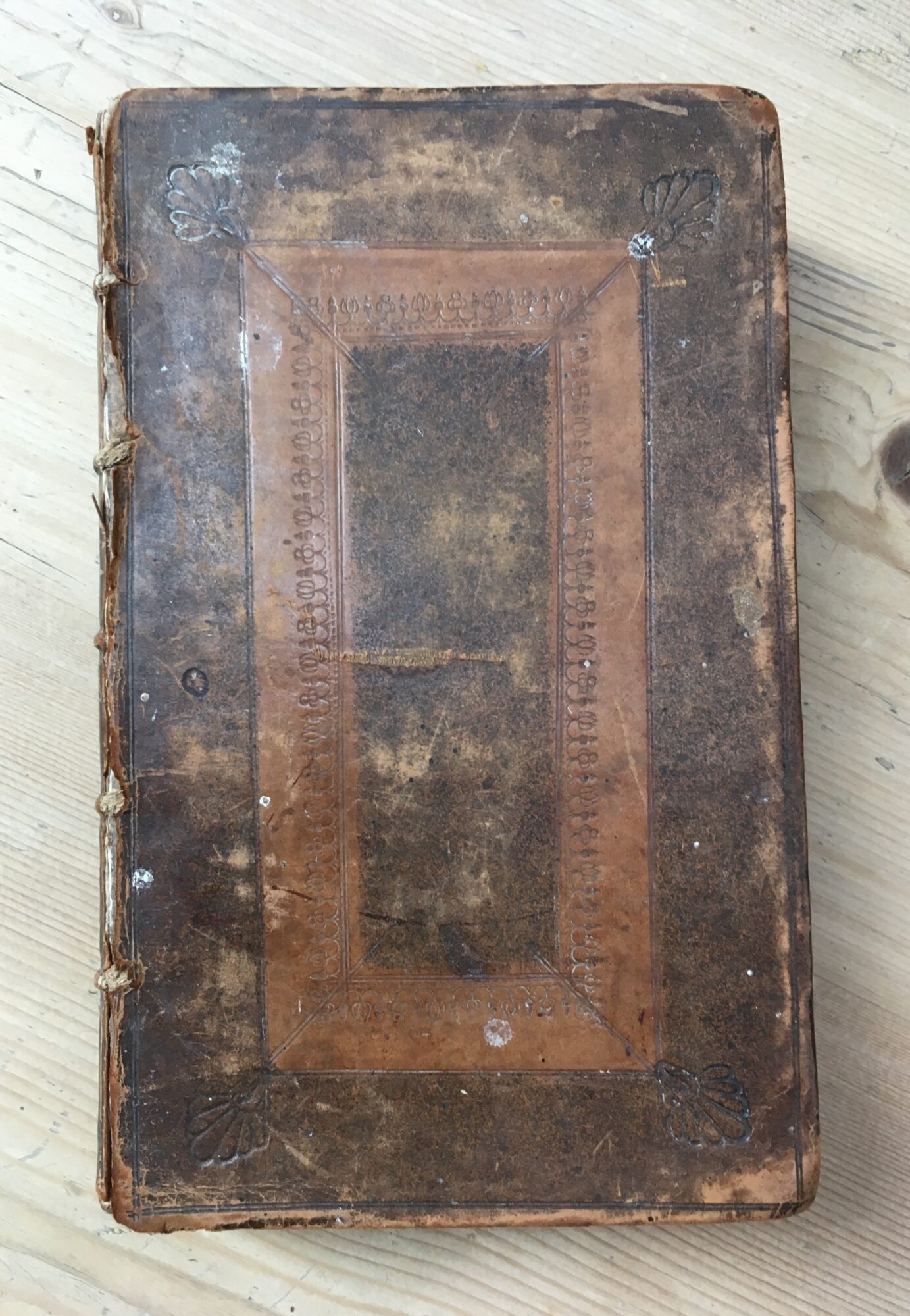

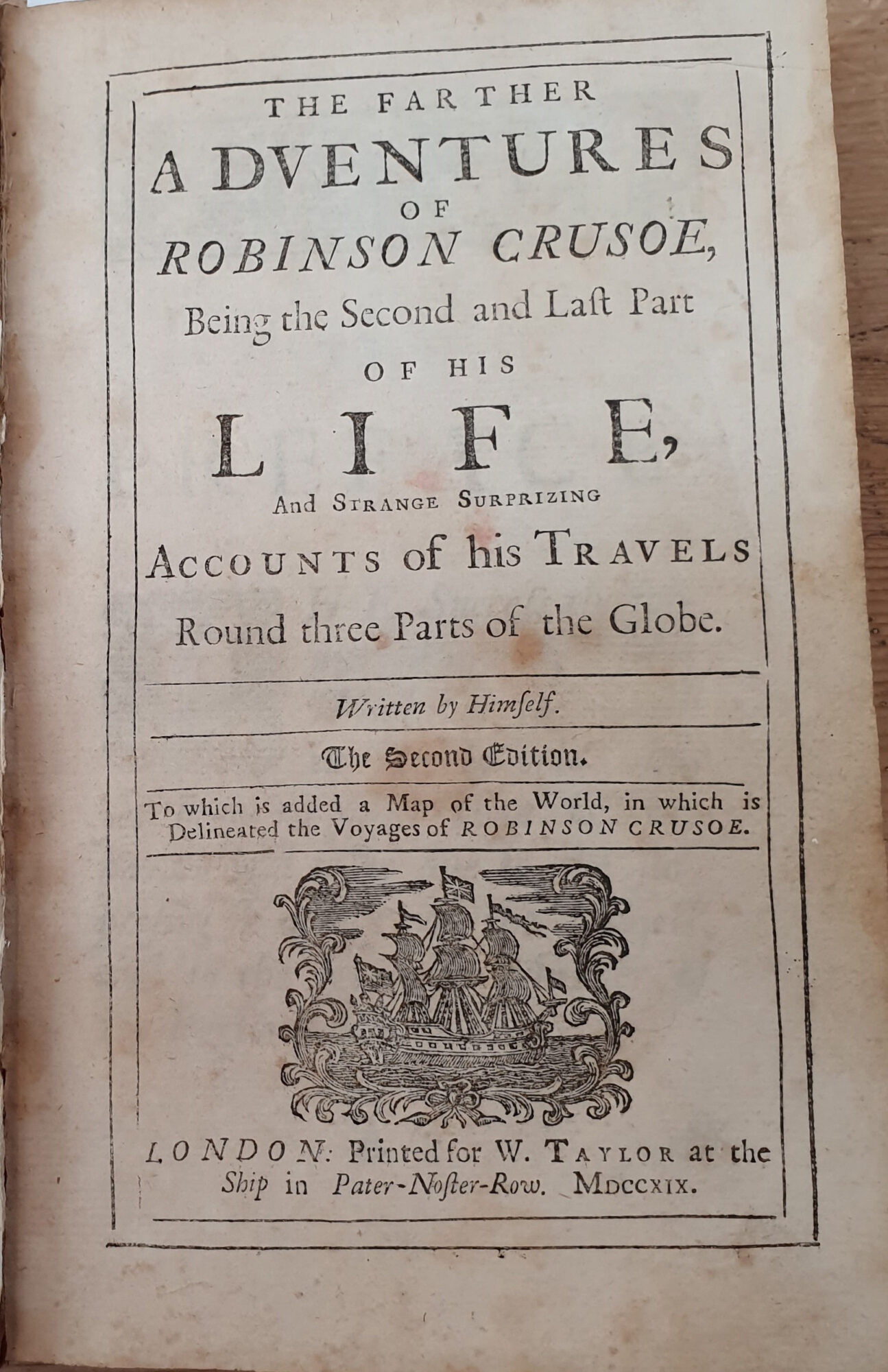

Are you ready to embark on another adventure? Robinson Crusoe certainly is as he sets out to explore the world once again in The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719). A copy of the sequel of the world-famous novel can be found at the Robinson-Library, a second edition printed already in 1720. Almost too delicate to touch, it is the library’s oldest possession. More than 300 years have left its marks on this true treasure.

.

When you open the book, a striking preface written by Defoe meets your eye in which he advertises the sequel being “as entertaining as the First”. Because the first volume was so popular, it was often pirated and abridged, however, and Defoe complained that this is “as scandalous as it is knavish and ridiculous, seeing that they may seem to reduce the Value, to strip it of all those Reflections, as well as religious and moral which are not only the greatest Beauties but are calculated for the infinite Advantage of the Reader” (‘Preface’ to Farther Adventures, 2-4). Yet what some regard as a publishing sin might actually have added to Crusoe’s success, since it spread Crusoe to a wider audience, and enabled the publication of a sequel in the first place. This enormous early popularity, and possibly Defoe’s anxiety about the “religious and moral” instructiveness of the Crusoe-story, led him to write a third volume of essays on topics like “Solitude” or “Honesty”. He need not have worried: most later editions well into the late 19th century combined the first two parts and sold them to eager readers. During this time Crusoe was a must-have for Victorian children. But if you buy a copy of Robinson Crusoe today, probably only the first part will be included. Why is this the case when both were so popular once?

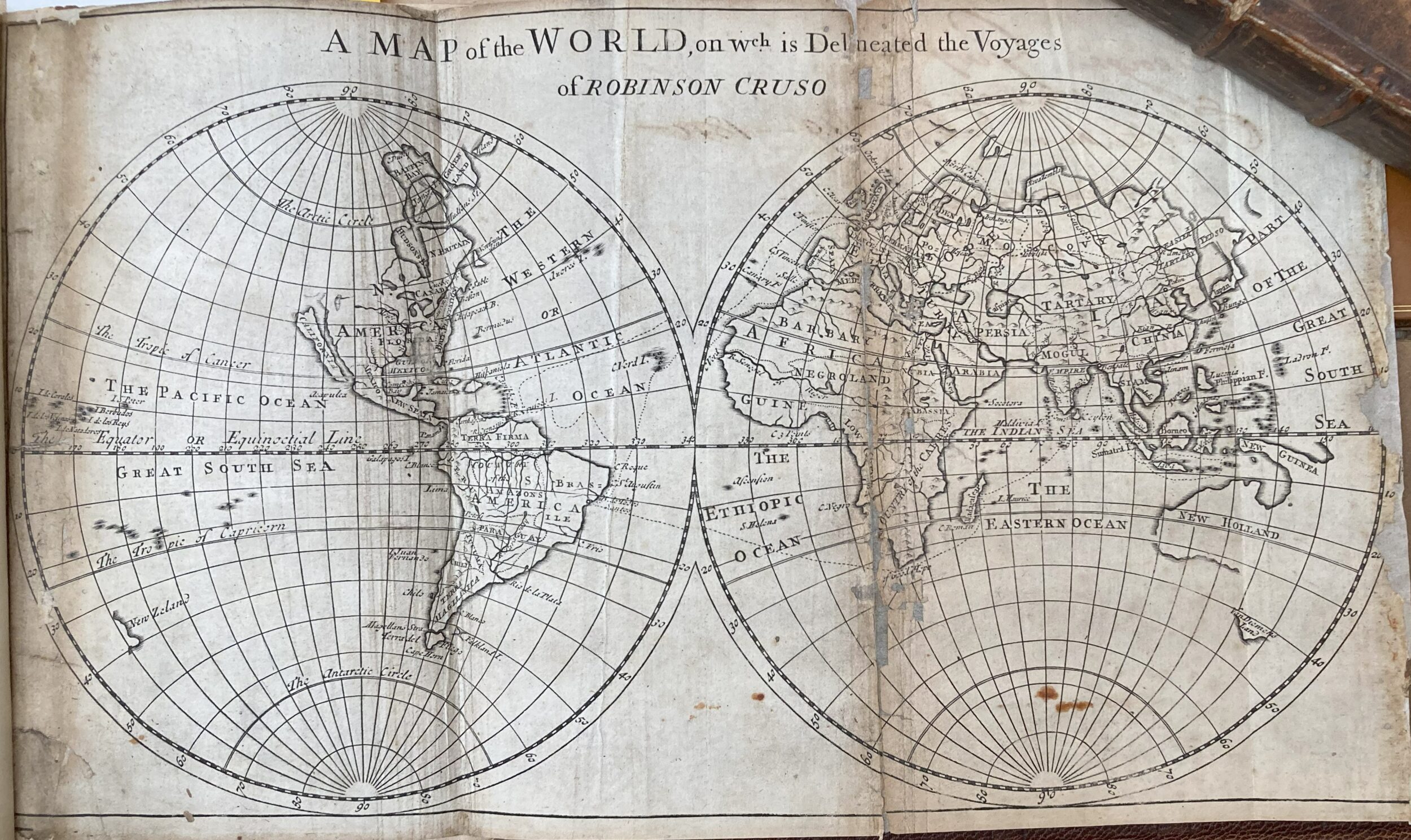

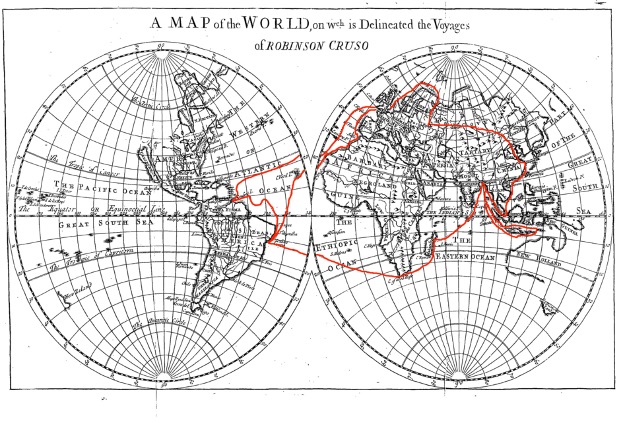

One reason might be the plot of Farther Adventures. This time Crusoe spends only a short time visiting his island and the settler community there, before he embarks on a voyage of trade that leads him to Madagascar, Bengal, Indonesia, Asia and Siberia. The volume is prefaced by a world map marking his travels across the glove in a red dotted line.

On his travels, Crusoe shows different, and conflicting sides of himself. From master of his desert island to expatriate merchant and cultural outsider, Crusoe passes through different roles. His character changes, too, and you will see him transform from a civilized, enlightened figure who admires indigenous cultures, languages and religions to a prejudiced, xenophobic Christian fanatic.

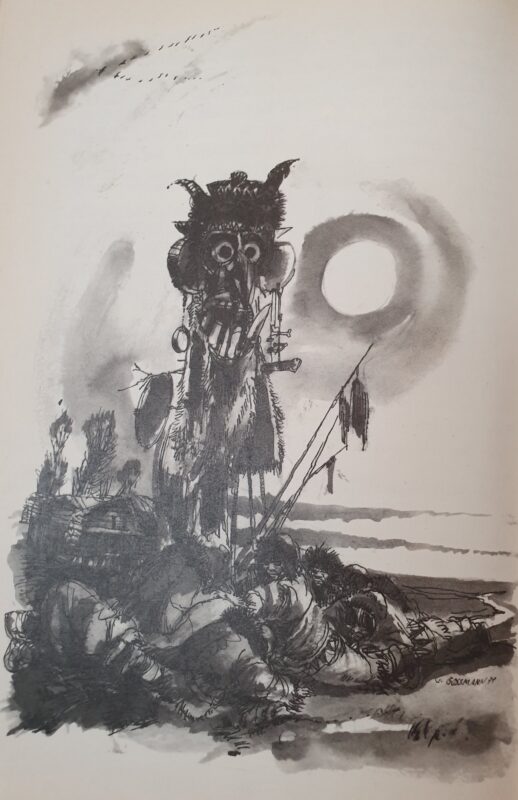

Along his journey in Russia, for example, he encounters Tartars worshipping an idol. He despises their heathenism and comes up with a cruel plan: “Well, says I, I’ll tell you a story: so I related the story of our men at Madagascar, and how they burnt and sack’d the Village there, and kill’d Man, Woman and Child, for their murdering one of our Men, just as it is related before; and when I had done, I added, that I thought we ought to do so to this Village” (Farther Adventures, 194). His reaction is quite out of character with his earlier personality since such cruelty, committed in Madagascar by his fellow shipmen, was initially despised by him: “However just our Men thought this Action, I was against them in it; and I always, after that Time, told them, God would blast the Voyage; for I look’d upon all the Blood they shed that Night to be Murther in them” (139).

The change from enlightened defender of indigenous people to their callous destroyer remains unexplained in the novel. But the story implies that his encounter with ancient Asian cultures and their resistance to either missionary or mercenary efforts might have jolted his belief in European superiority. This was perhaps an uncomfortable insight at a time when, from the late nineteenth century onwards, Britain had to increasingly deal with the fallout from its empire building, and even more so around the middle of the twentieth century when, amidst decolonisation, Farther Adventures dropped from sight. Did publishers not want to confront the readers with an evil Crusoe? Did the vastness of a globalized world of travel, trade and cultural diversity prove too disturbing? Did readers seek refuge in the simple world of the First Part’s island-episode, in which Crusoe reigned supreme? Too many answers arise from one simple question. Yet the most important question remains: Are you ready to go on board with Robinson Crusoe again?

Text: Anna Strobel

Sources:

- Defoe, Daniel. The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: Being the Second and Last Part of his Life. Bd. 2 von The Novels of Daniel Defoe, hg. von W.R. Owens und P. N. Furbank. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Free, Melissa. “Un-erasing ‘Crusoe’: Farther Adventures in the Nineteenth Century.” Book History 9 (2016): 89–130.

- Howse, Dan. “Robinson Crusoe, Improvement and Intellectual Piracy in the Early Enlightenment.” In Robinson Crusoe in Asia, ed. by Clark and Yukari Yoshihara. Singapur: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, 87–108.