The Black man submitting to his White master, Robinson Crusoe teaching Man Friday to say “yes”, “no” and “master”. These images are connected to critical readings of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe as a novel about colonialism. Many illustrated editions feature the key scene of colonial submission. But one nineteenth-century Robinsonade reverses its message: The Black Crusoe by French author Alfred Séguin (Le Crusoe Noir, 1877; English translation in 1879) puts a Black man in the position of the enlightened Master, and makes a White man dependent on his help and wisdom. The hero Charlot has even read the original Robinson Crusoe and reflects on the novel by saying that he is “a black Crusoe” and by modelling himself on the character.

Charlot, a young Black slave, was brought up together with his white master George de Merville in the Caribbean. But while Charlot is smart and kind, George is cruel and abuses his position as master to make Charlot’s life very difficult. Two separate shipwrecks cast them away on the same island: Charlot has already lived there for a few years when his foster-brother suffers the same fate. Charlot rescues him, nurtures him and teaches him the qualities of kindness, generosity and patience. George eventually becomes ‘civilized’ by this sentimental education and learns to respect and love Charlot. Together, they experience some adventures before finally returning home safely.

The Black Crusoe was revolutionary for its time: while slavery had been abolished in the French and British colonies as well as the United States, many still believed that Black people were inferior and deserved to be slaves. Charlot however is educated, well-spoken, kind and brave, willing to share his knowledge with others. He presents all the qualities expected of an enlightened, Christian White man with just one difference: his skin colour. Indeed, the fact that he received the same education as a white boy but profited from it much more breaks the belief in a natural White superiority.

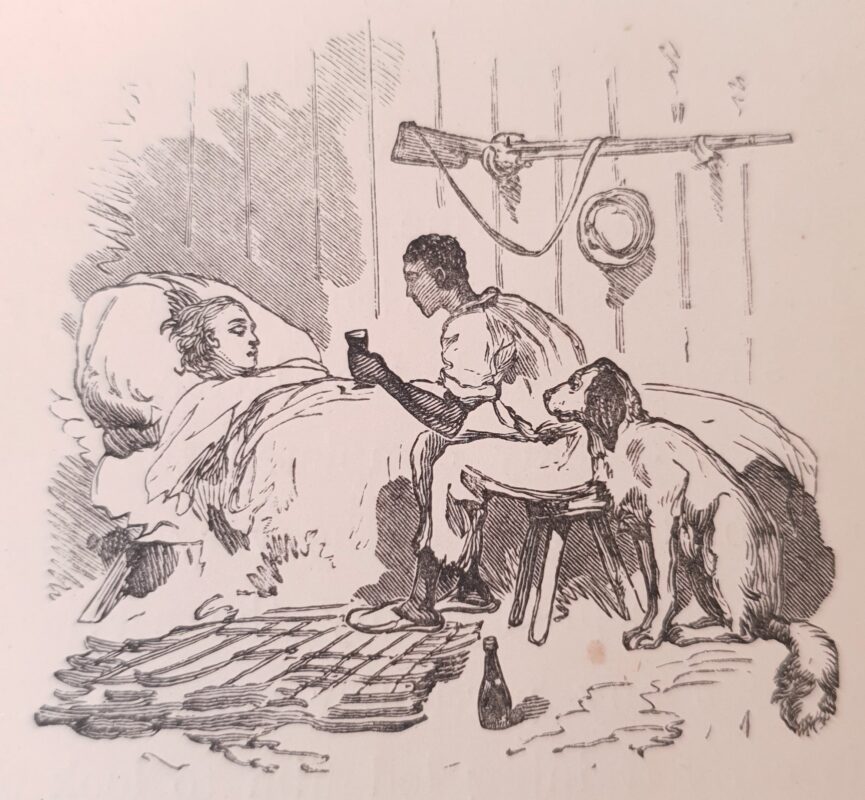

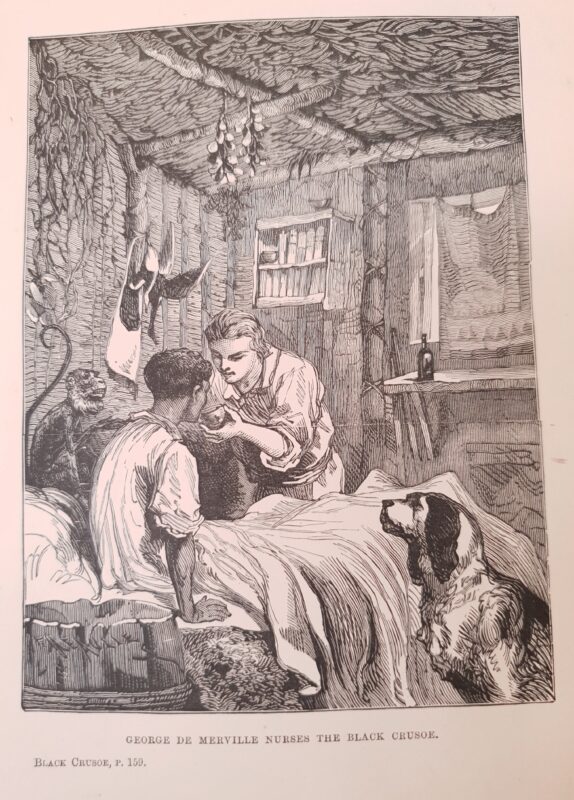

At the centre of The Black Crusoe is the education of the ‘savage’, yet in this novel the savage is the white man George: he lacks not knowledge but morality. The story shows how he develops and responds to what Charlot has to teach. At the beginning, Charlot helps a stranded George; in the end, George helps a sick Charlot.

Both illustrations focus on George’s progress: he is the central figure, both as the helped and as the helper. Yet the background tells us a lot about Charlot: the rifle on the wall signals his ability both to defend himself and to give protection; the books on the shelf show his love of learning. The dog as a faithful companion indicates what both boys might become for each other.

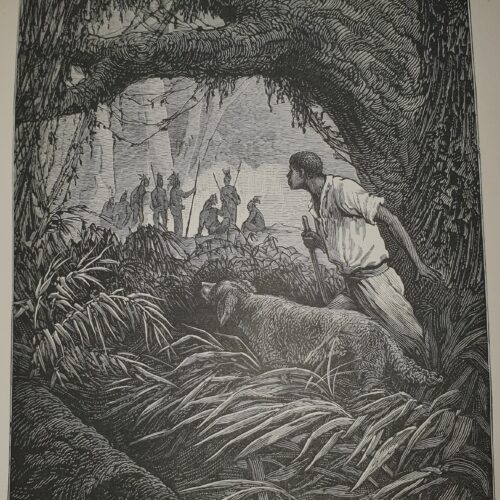

Yet The Black Crusoe also reproduces a problematic racial hierarchy. While a Black person is shown as equal to a White one, another race is still shown as naturally inferior: Charlot himself is a colonizer and sees the natives of the island as ‘savages.’ He assumes, as Robinson Crusoe did, that they are cannibals and is portrayed observing them suspiciously, as a White colonizer would.

Later on, he attempts to educate them. This time, Charlot is presented as culturally superior, and his teachings are a necessary process of ‘civilization.’ Overall, The Black Crusoe is very much a child of the nineteenth century: it attempts to challenge the racist ideology of colonialism, but is still miles away from later Robinsonades like Michel Tournier’s Friday (1968) or J.M. Coetzee’s Foe (1982) that actually reverse the roles and race hierarchies of Defoe’s novel.

Text: Larissa Bison

Sources:

- Carey, Daniel. “Reading Contrapuntally: Crusoe, Slavery and Postcolonial Theory”. In The Postcolonial Enlightenment: Eighteenth-Century Colonialism and Postcolonial Theory, ed. by Daniel Carey and Lynn Festa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, 105–136.

- Boyle, Charles. “Robinson Crusoe at 300: Why it’s time to let go of this colonial fairytale.” The Guardian, 19 April 2019, www.theguardian.com/books/2019/apr/19/robinson-crusoe-at-300-its-time-to-let-go-of-this-toxic-colonial-fairytale. Last access 31 June 2024.

- Séguin, Alfred. The Black Crusoe. Illustrations by H. Scott, F. Meyer, F. Méaulle. London: Marcus Ward, 1879.

- Todd, Dennis. “Robinson Crusoe and Colonialism”. In The Cambridge Companion to ‘Robinson Crusoe’, ed. by John Richetti. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018, 142–156.