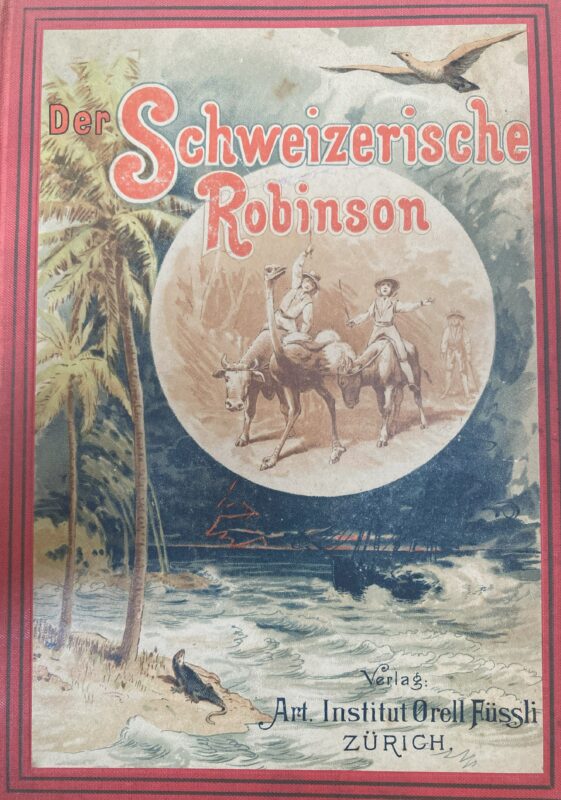

The Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss (1743–1818) tells the story of a pastor’s family of six who leave Switzerland around 1800 for a missionary assignment in the South Pacific. In this explicit adaptation of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, the characters in the ‘family Robinsonade’ are also shipwrecked and from then on live as the only survivors on a deserted island.

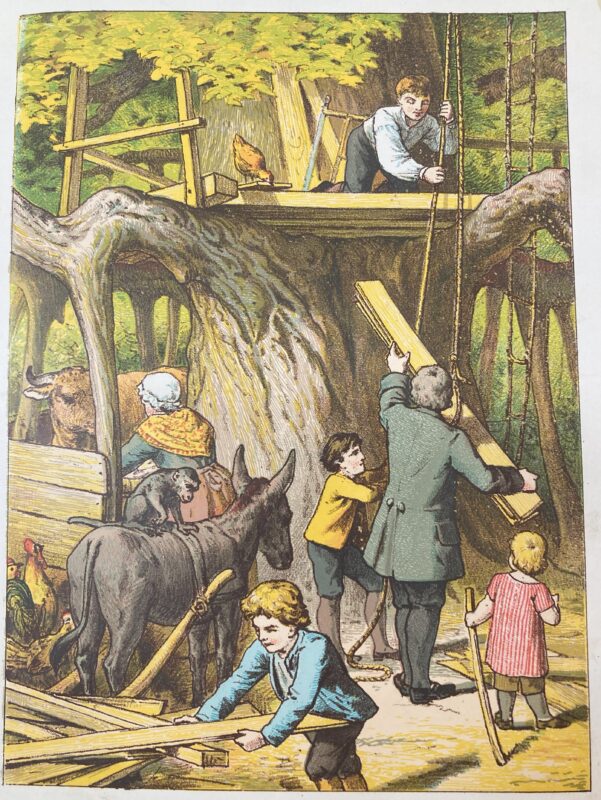

Four volumes (first published between 1812 and 1827, Orell Füssli Zurich) describe ten years of island life in which the Robinson family makes a home and increasingly expands it. The initially unfamiliar island space is gradually explored, classified and named; animals are killed or tamed, the landscape is reshaped. The family builds encampments all over the island, with “Felsenheim” – an eight-room apartment carved into the rock with a veranda, a garden, and surrounding fields – representing the luxurious highlight and a veritable bourgeois idyll. It is protected from the rest of the island by the “Schakalbach”, which they traverse via drawbridge. The numerous adventures and activities of their new family life are closely linked to the upbringing and education of the sons.

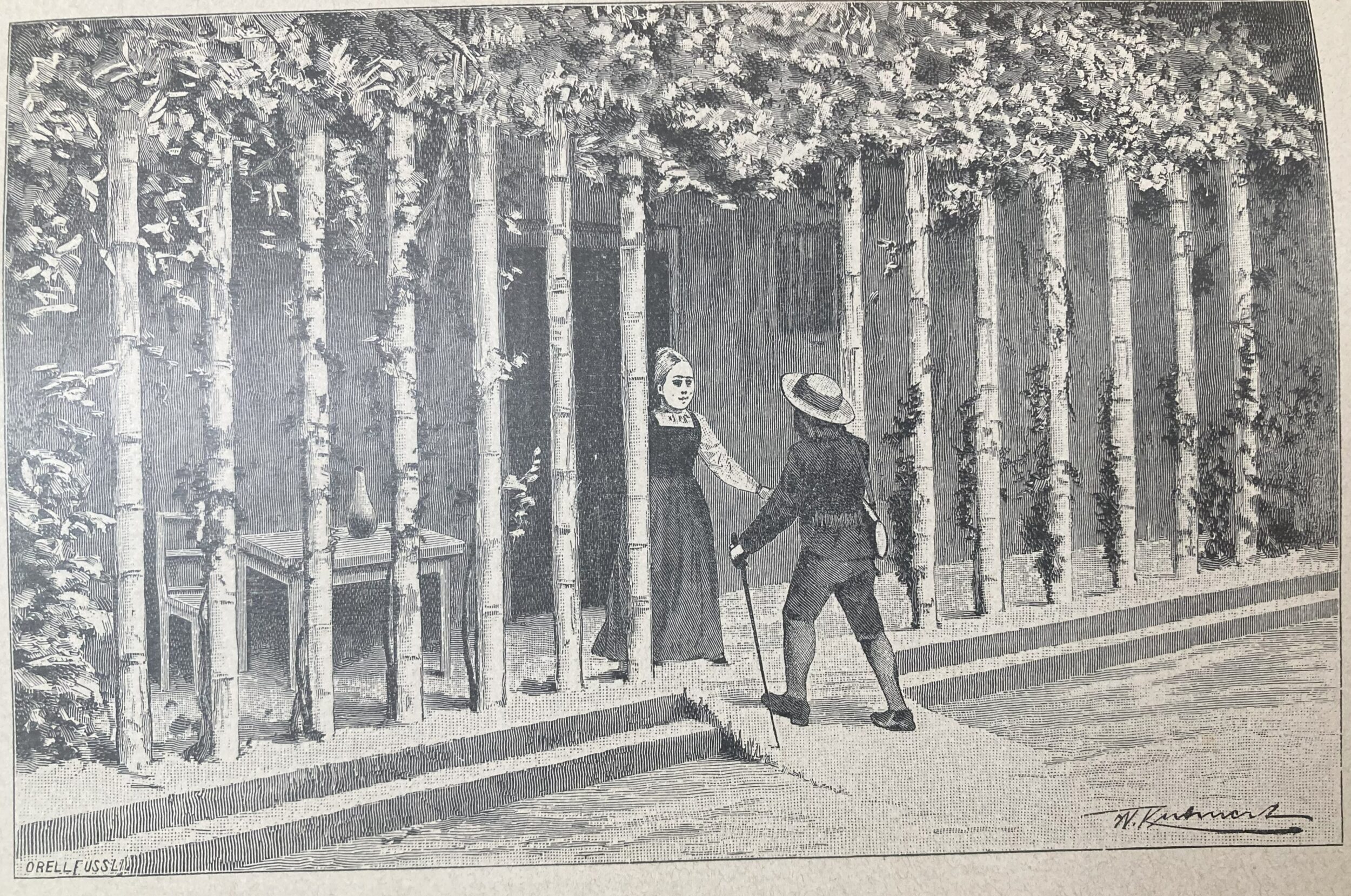

After ten years, they encounter another human for the first time on the island: another shipwrecked young woman, Jenny Montrose from England, who was able to rescue herself onto another part of the island. Her story remains a side note, but it is curious. Using very simple means and tools – woven baskets, collected seashells and repurposed seal bladders – she manages to overcome challenging situations while preserving resources. Her way of working thus contrasts with the Robinson family’s wasteful and crude ways of engaging with their environment and points to alternative Robinsonades. Shortly after Jenny’s appearance, a merchant ship coincidentally finds the remote island, allowing the family to reconnect with the rest of the world. Two of the four sons decide to return to Europe alongside Jenny; the other two stay behind with their parents in their newly founded colony “New Switzerland”, which is even enlarged by some of the ship’s passengers.

Wyss created a setting for his novel in which he can focus entirely on the upbringing and education of his sons, “separated from the world”, “but still […] making use of its useful inventions” (6). The text is thus strongly inspired both by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s interpretation of Robinson, in which the novel is declared to be educationally valuable and therefore suitable reading for children, and by Joachim Heinrich Campe’s adaptation of the novel for children, Robinson the Younger (1779/80). Wyss’ version, however, is innovative in the sense that children are placed in Robinson’s situation for the first time. Adventure and education are thus linked: On their long forays across the island, the father and his sons discuss a variety of topics that also concerned Defoe’s Robinson: How should one shape one’s life? What is God’s plan? What is the purpose of learning new things and what is the relationship between humans and animals?

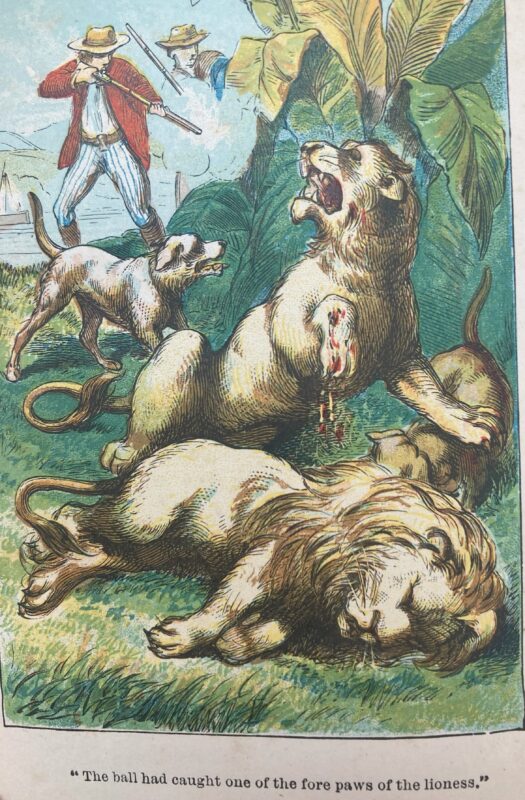

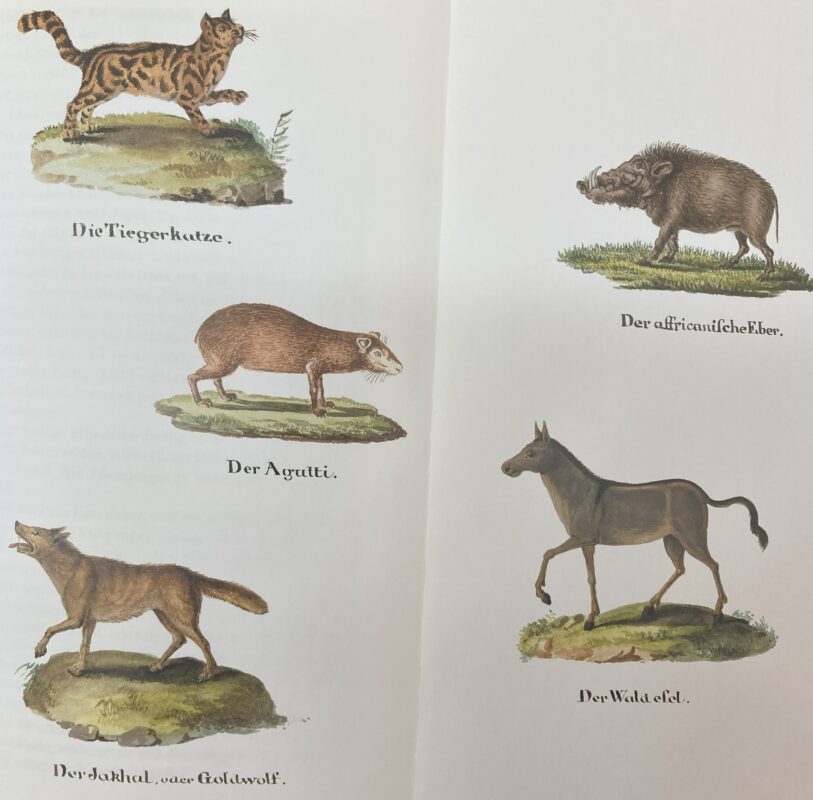

The amount of technical and scientific knowledge about the world that Wyss – who was well-read and widely interested himself – has the family’s father teach is impressive. In this teaching, however, the actual environment of the island itself is not considered. Instead, the Robinsons encounter animals, plants, and minerals from around the world concentrated on the island. Their knowledge about nature and the cultural techniques from different countries and ethnicities regarding hunting, livestock farming, obtaining and preparing of food, building tools and buildings, and much more mirror the general knowledge collected in the travel and research literature that was popular at the time. We know that Wyss used the records of J. R. Forster, a natural scientist and companion of James Cook, as a source (Kortenbruck-Hoeijmans 1999, 24).

With this accumulation of world knowledge – and in combination with the more than 60 accompanying illustrations of animals, tools, plants and landscapes, the Swiss Robinson is also reminiscent of the genre of the encyclopaedia that was new at the time. The manuscript contains a total of 164 different animal species, 102 plant species and 130 episodes in which the production of clothing, tools and food are described in great detail and in some cases even illustrated.

Accordingly, Wyss’ pedagogical attitude also enthusiastically affirms curiosity about nature and foreign cultures. This contrasts with Campe, who follows Defoe’s original more: There, Robinson’s wanderlust is a sign of his lack of discipline and the island figures as a punishment and as a place for reform (Rutschmann 2002, 166). The Swiss Robinson is thus not only a particularly significant example for how influential the ‘pedagogical strand’ of Robinson Crusoe ’s reception was at the end of the 18th century. It is also a cultural and historical testimony to a period marked by the Enlightenment and the systematisation of knowledge, as well as by the violent colonial expansion of Europe.

Today, the Swiss Robinson is considered as one of the most successful children’s book adaptations of Robinson Crusoe. Alongside Johanna Spyri’s Heidi, it is also the Swiss children’s book that has been distributed the most widely on an international scale. Between 1811 and 1980, more than 600 different editions and adaptations were published in various media forms – books, films, radio plays – in more than twenty languages (Rutschmann 2002, 159 and Kortenbruck-Hoeijmans 2016, 1121). Especially the Hollywood film adaptation The Swiss Family Robinson (1960), directed by Ken Anakin, was extremely popular and is a cult film until today.

Text: Sina Chiavi

Translation: Timothy Holden

Sources:

- Kortenbruck-Hoeijmans, Hannelore. Johann David Wyß’ “Schweizerischer Robinson”. Zeitgeistdokument an der Wende zum 19. Jahrhundert. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider-Verlag Hohengehren, 1999.

- Kortenbruck-Hoeijmans, Hannelore. “Eine Reise zum Schweizerischen Robinson”. In Johann David Wyss: Der Schweizerische Robinson oder der schiffbrüchige Schweizer-Prediger und seine Familie, hg. von Christian Döring. Berlin: Die Andere Bibliothek, 2016, 1121–1142.

- Rutschmann, Verena. “‘Der Schweizerische Robinson’ – eine erzählte Enzyklopädie”. In Populäre Enzyklopädien: Von der Auswahl, Ordnung und Vermittlung des Wissens, hg. von Ingrid Tomkowiak. Zürich: Chronos, 2002, 159–173.

- Rutschmann, Verena. “‘Der Schweizerische Robinson’ – eine erzählte Enzyklopädie”. In Populäre Enzyklopädien: Von der Auswahl, Ordnung und Vermittlung des Wissens, hg. von Ingrid Tomkowiak. Zürich: Chronos, 2002, 159–173.

- Wyss, Johann David, Der Schweizerische Robinson oder der schiffbrüchige Schweizer-Prediger und seine Familie, hg. von Christian Döring. Berlin: Die Andere Bibliothek, 2016.