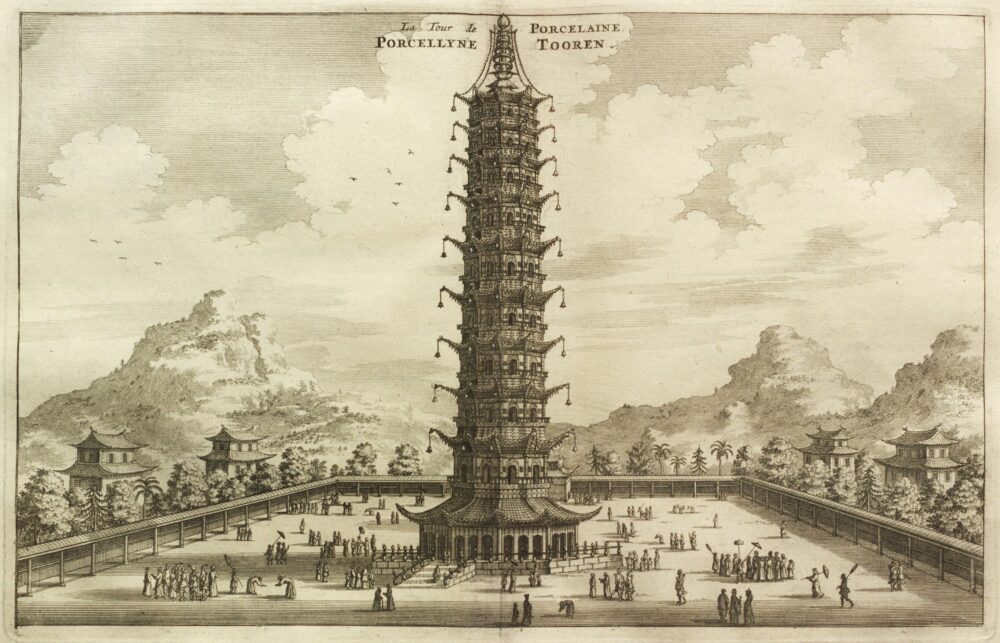

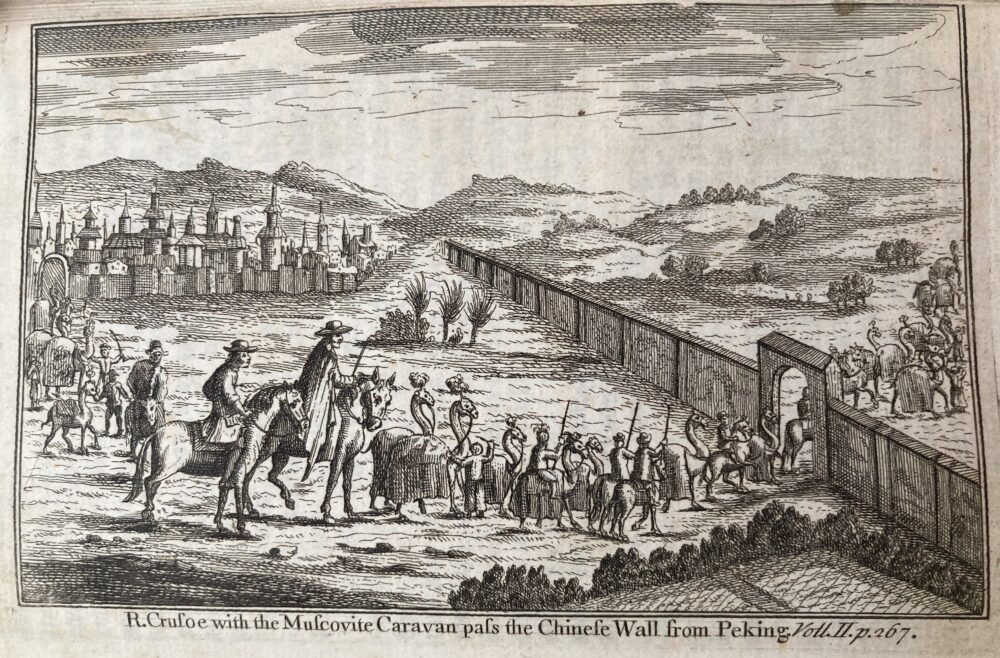

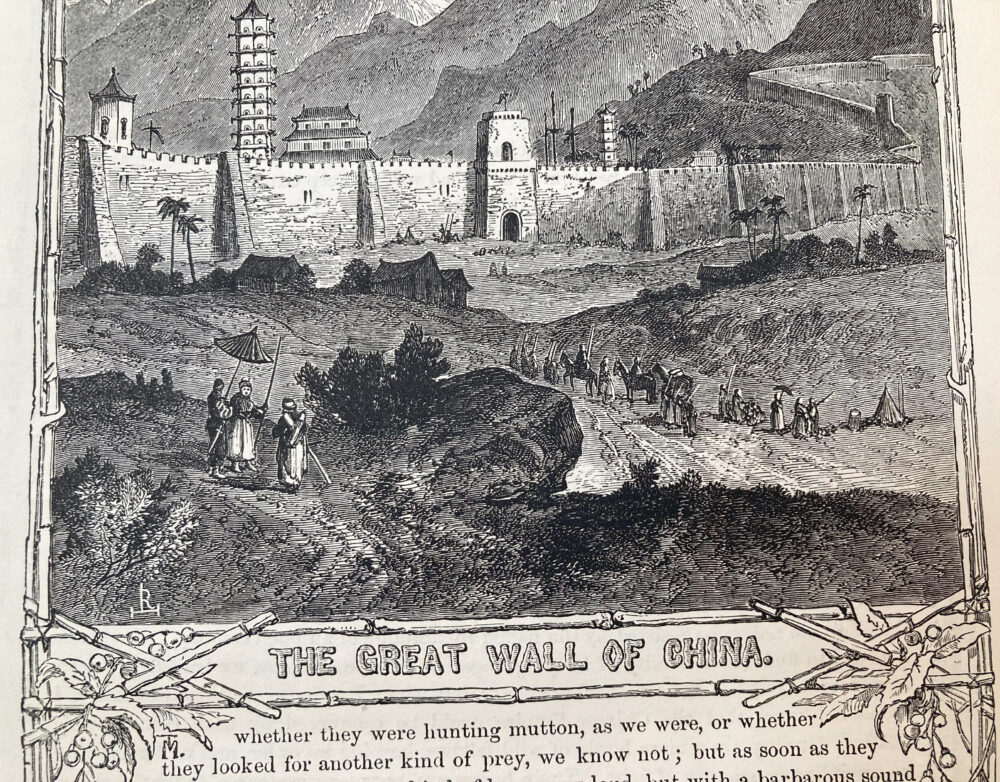

Did you know that Robinson Crusoe also travelled to China? After his return to England at the end of Part One, he is eager to see his island again and to explore the world. Like many eighteenth-century merchants, he travels to the Far East. After a long sojourn in the Bay of Bengal and Indonesia, he enters China through its southern shore with some Portuguese sailors and a Jesuit priest. Together, they journey to the north and stop by the two most famous cities in that region – Nanquin (Nanjing) and Peking (Beijing). Crusoe’s companion, Father Simon, is very fond of China. In his opinion, Peking is the “greatest city of the world” that “your London and our Paris put together cannot be equal to” (Farther Adventures, 169). Crusoe himself is fascinated by a house made entirely of porcelain, a material which Europeans were not able to produce themselves, as he grudgingly admits (181). His description is likely inspired by contemporary images of the famous porcelain tower at Nanjing.

Back in eighteenth century, China was famous for luxury goods such as porcelain, tea and silk. The import and consumption of such goods greatly influenced Britain’s ideas of civilization and aesthetics. It can be said that China had a considerable cultural impact on Britain. China was also seen as a giant market for business. When one of his travel companions tells him about frequent trading between China and Europe – “there was a great Caravan of Muscovite and Polish Merchants in the City” – Crusoe eagerly makes plans for joining in the Asia trade: “we might be able to purchase all Sorts of the Manufactures of the Country, and withal, might possibly find some Chinese Jonks or Vessels, from Tonquin, that would be to be sold, and would carry us and our Goods, wherever we pleas’d” (Farther Adventures, 178, 172).

In reality however, the Chinese market created problems for the British economy. China exported exotic luxury goods for a high prize while remaining largely uninterested in European produce. In New Voyage Around the World (1725), Defoe articulated his criticism of the export deficit characteristic of the Asia trade. The passage also registers a mortifying sense of inferiority: “[W]e carry nothing or very little but money there, the innumerable nations of the Indies, China, &c., despising our manufactures and filling us with their own.” (New Voyage, 155) Crusoe seems to share this sense of economic inferiority, and it registers increasingly in his deep resentment toward Chinese culture: “When I come to compare the miserable People of these Countries with ours, their Fabricks, their Manner of Living, their Government, their Religion, their Wealth, and their Glory as some call it, I must confess, I do not so much as think it is worth naming, or worth my while to write of, or any that shall come after me to read.” (Farther Adventures, 173) Is this demeaning comparison an accurate description of China, or an attempt at maintaining Crusoe’s belief in the superiority of European culture?

Crusoe is clearly no admirer of eighteenth-century China. However, in modern China, Robinson Crusoe remains to be one of the most popular novels. The novel was introduced to China already in the late Qing Dynasty (end of nineteenth century until early twentieth century). Robinson Crusoe was read less for literary pleasure than for didactic purposes. Based on different educational purposes in the Chinese context, Crusoe’s image changed considerably. For example, during the Anti-Japanese War (1937–1945), Crusoe’s story was used as an example to make children aware of the dangers of imperialism and colonialism. After the war, the country’s economy was shattered and everything had to be rebuilt. Therefore, in the post-war period, Crusoe’s story was used as a propaganda tool to encourage young people to get involved in developing the country. The adaptations of the story thus focused on Crusoe’s efforts to survive on the island, while the colonial aspect of the story was obscured. Today, Robinson Crusoe is one of the readings for secondary school students required by the Chinese Ministry of Education.

In the Robinson Library, the Asian versions of Robinson Crusoe are mostly those modified for young readers. This item, for example, was published by Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, founded by Beijing Foreign Studies University in 1979, one year after China’s Reform and Opening-up. The book belongs to the “Bookworm” series – a name that is well known among school students in China. The aim of this series is to help English learners with limited vocabulary to read English novels. After China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, a boom in English learning took place. Twenty years on, this book can easily be found on the shelves of a secondary or high school classroom.

Text: Peiwen Liang

Sources:

- Defoe, Daniel. A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before, ed. by George A. Aitkin. London: Dent, 1902.

- Defoe, Daniel. The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe; Being the Second and Last Part of his Life. Vol. 2 of The Novels of Daniel Defoe, ed. by W.R. Owens and P. N. Furbank. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Kyung Min Eun. China and the Writing of English Literary Modernity, 1690–1770. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Markley, Robert. “Crusoe’s Farther Adventures and the Unwritten History of the Novel.” In A Companion to the Eighteenth-Century English Novel and Culture, ed. by Paula R. Backschneider and Catherine Ingrassia. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. 25–47.

- Richetti, John. “Eurocentric Crusoe: The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.” Études Anglaises 72.2 (2019): 213–224.

- Zhang, Xinke (张新科). “清末民国语文教育阐释《鲁宾逊漂流记》:违慈训少年作远游遇大风孤舟发虚想”. 文汇报, 08 June 2018; https://wenhui.whb.cn/zhuzhan/xueren/20180608/200273.html (last access 07 Jul 2024).