Imagine someone removed Robinson Crusoe from his tropical island and placed him into the colds of Greenland to create an arctic Robinson. That might be a concept that seems hard to grasp. But two books in the collection, the autobiographical account by Ejnar Mikkselsen, An Arctic Robinson (German: Ein arktischer Robinson, 1913), and the adventure novel Nuvat the Brave: An Eskimo Robinson Crusoe (1934) by Radko Doone, do precisely that.

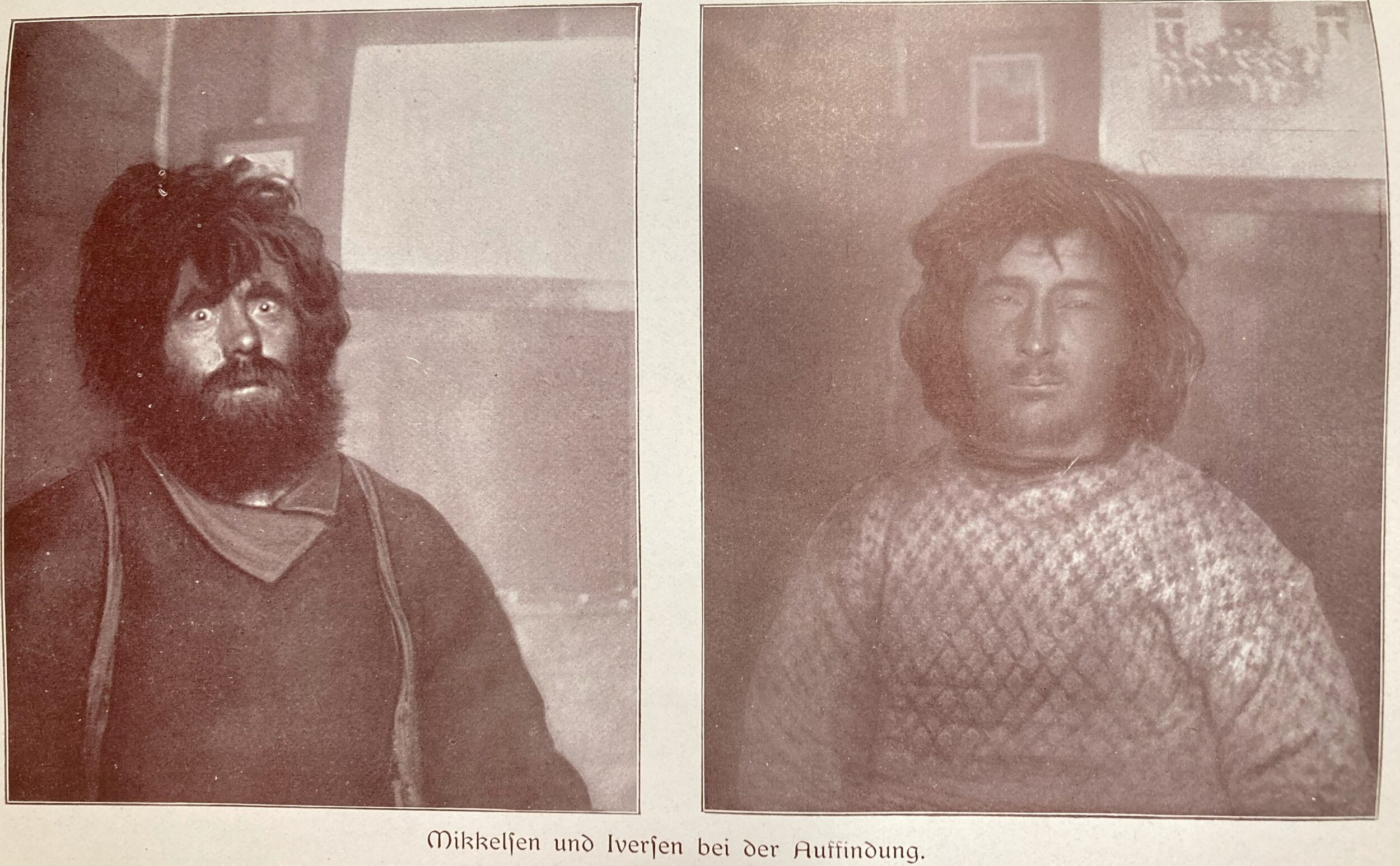

These two arctic versions of Crusoe – Ejnar Mikkelsen himself, a Danish polar explorer and captain of a ship, and Nuvat, a fictional 12-year-old Inuit – both set out into distant cold lands. While Mikkelsen, together with one of the men from his crew, embarks on the journey with the goal to explore unknown parts of Greenland, Nuvat gets separated from his family due to an ice floe breaking off and sending him into the arctic sea with no company but his dog. Both end up in uninhabited, cold, far-off places where they have to adapt to the extreme environment.

Neither cast-away makes any human contact during their isolation. This is an interesting twist on Defoe’s original version, because the absence of a foreign civilization removes the aspect of colonialism from the story, which is otherwise highly prominent in Robinson Crusoe. Moreover, both Mikkelsen and Nuvat have immense respect for the environment they find themselves in. One scene in Nuvat the Brave is particularly instructive, which echoes a famous passage from Defoe’s novel in which Crusoe surveys his island from a hilltop and boasts “I was Lord of the whole Manor; or if I pleas’d, I might call myself King, or Emperor over the whole Country which I had Possession of.” (Robinson Crusoe, 94). The narrator of Nuvat points out that while “any other boy, looking from a hilltop over a solitary island on which he was the only human being, might have felt like a king gazing over his kingdom, […] such a thought never entered Nuvat’s head.” (Nuvat, 75)

The contrast between Crusoe and Nuvat is further intensified by the fact that he is an Inuit. The Inuit are indigenous to the arctic and represent the colonized. The Danish colonization of Greenland began with the foundation of the Royal Greenlandic Trading Company in 1721, around the same time when Defoe wrote his Crusoe-stories; it continues until today. And while the protagonist of Mikkelsen’s Arctic Robinson is a Danish citizen and therefore technically represents the colonizer, this role is never acknowledged in the narrative: perhaps because this colonial heritage had already become contested and difficult by the time the novel was written, or perhaps because the narrative tries to establish an altogether different relation to Inuit culture. Both texts moreover introduce a multitude of Inuit practices by describing them in detail, and their heroes both return home, having gone through an immense amount of personal growth and having gained a better understanding of the arctic environment.

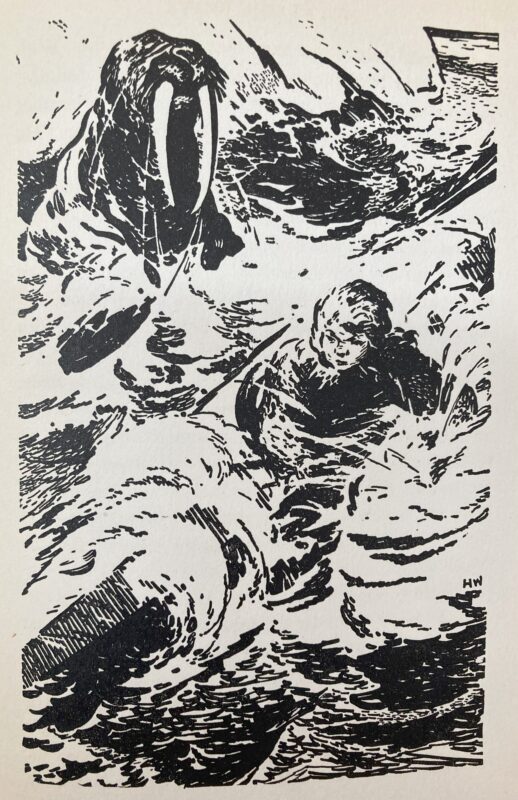

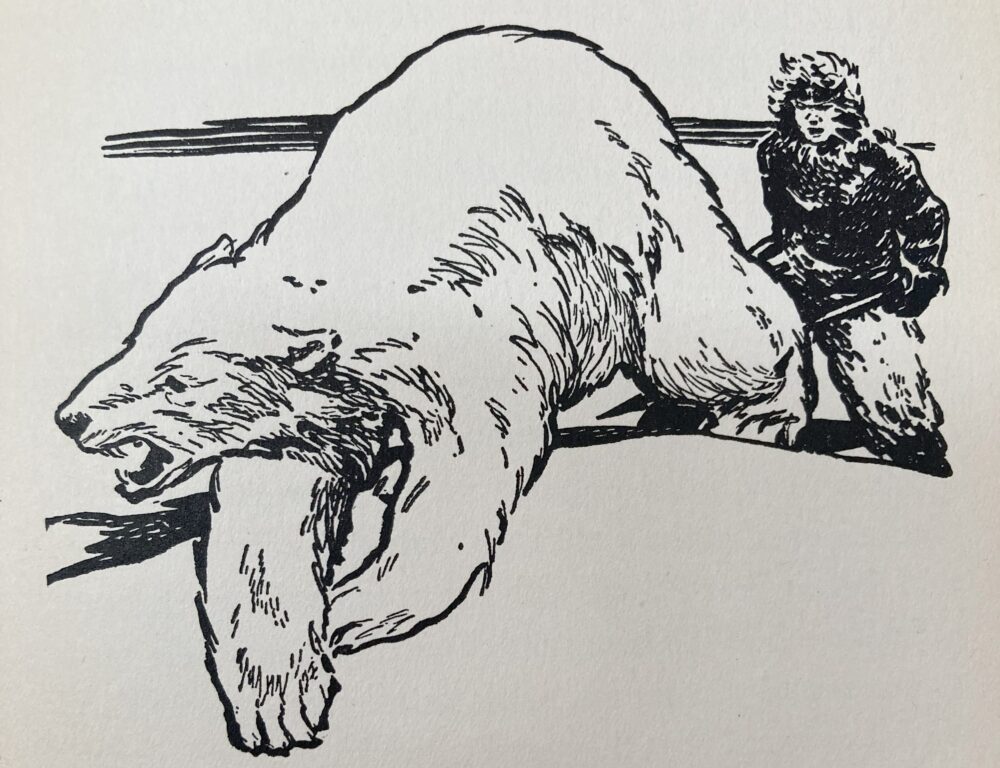

Yet before they are able to make their way back, they each have to adapt to the harsh arctic environment itself. Unlike Crusoe who, in spite of some hardships, lives well on his tropical island, surviving in the icy world of Greenland is far more challenging: the water in which these arctic Robinsons have to hunt seals for nourishment is freezing cold, bearing a high risk for hypothermia. And unlike Crusoe, whose rifle allows him to fend off any dangers, the arctic sea holds insurmountably dangerous creatures, such as whales and walruses, while deadly polar bears roam the ice. Encounters with them turn out rather uncomfortable for both Nuvat and Mikkelsen,highlighting the vulnerability of the human body isolated from civilization and its technological props. As such, these texts thus also have an ecocritical message that urgently calls to us today as the polar ice caps keep melting under the impact of human technology.

Text: Sofia Zumsteg

Sources:

- Doone, Radko. Nuvat the Brave: An Eskimo Robinson Crusoe. Philadelphia, 1934.

- Mikkelsen, Ejnar. Ein arktischer Robinson. Leipzig, 1913.

- Boyle, Tiffany, and Jessica Carden. “Nordic Colonialism and Indigenous Peoples.” In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism, ed. by Immanuel Ness and Zak Cope. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, 2101–2107.

- Naum, Magdalena, and Jonas M. Nordin (eds.). Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: Small Time Agents in a Global Arena. New York: Springer, 2013.