Illustrations have been an important dimension of Robinson Crusoe‘s popular appealsince it was first published over 300 years ago. Many of the works and artefacts in the collection have beautifully illustrated covers, as well as maps and drawings hidden among the pages. There are also several items which are not books, but rather works of visual art or new interpretations of the form.

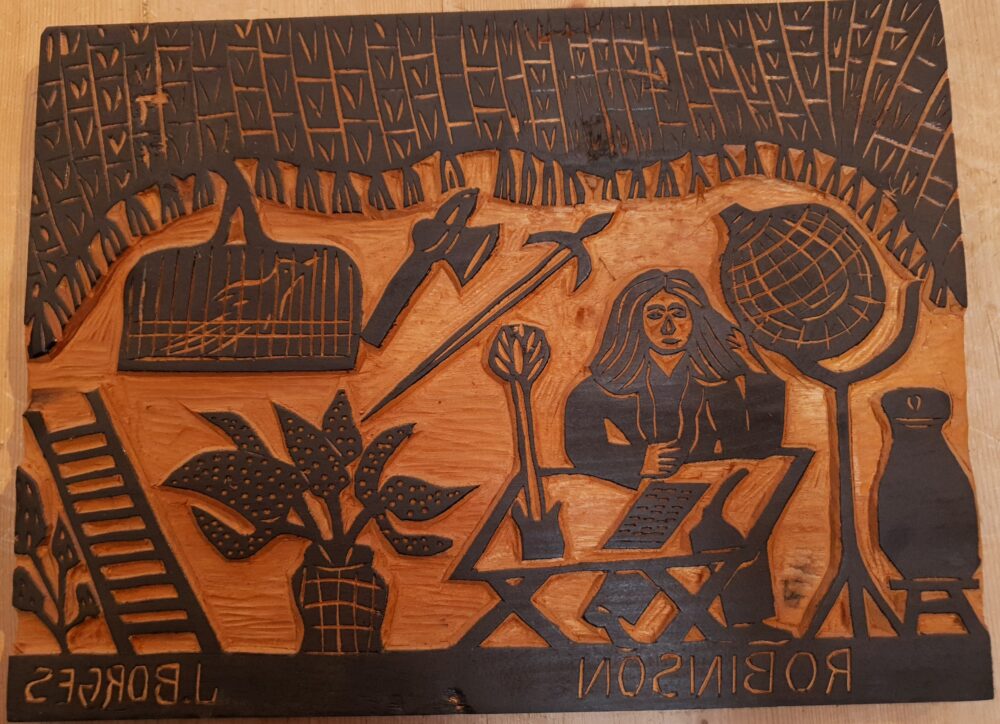

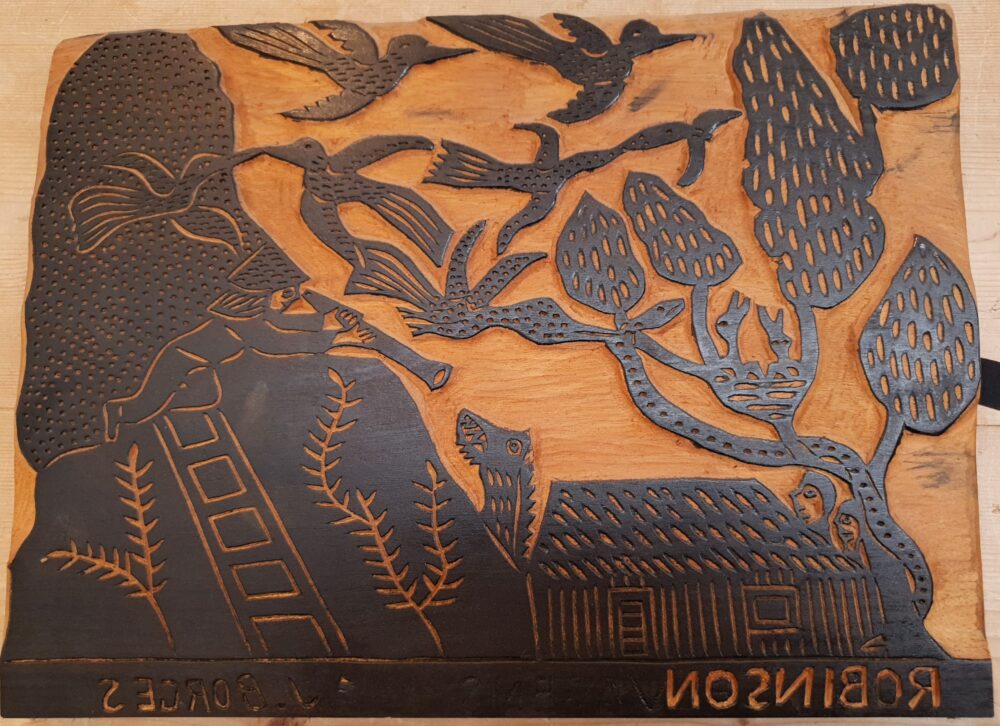

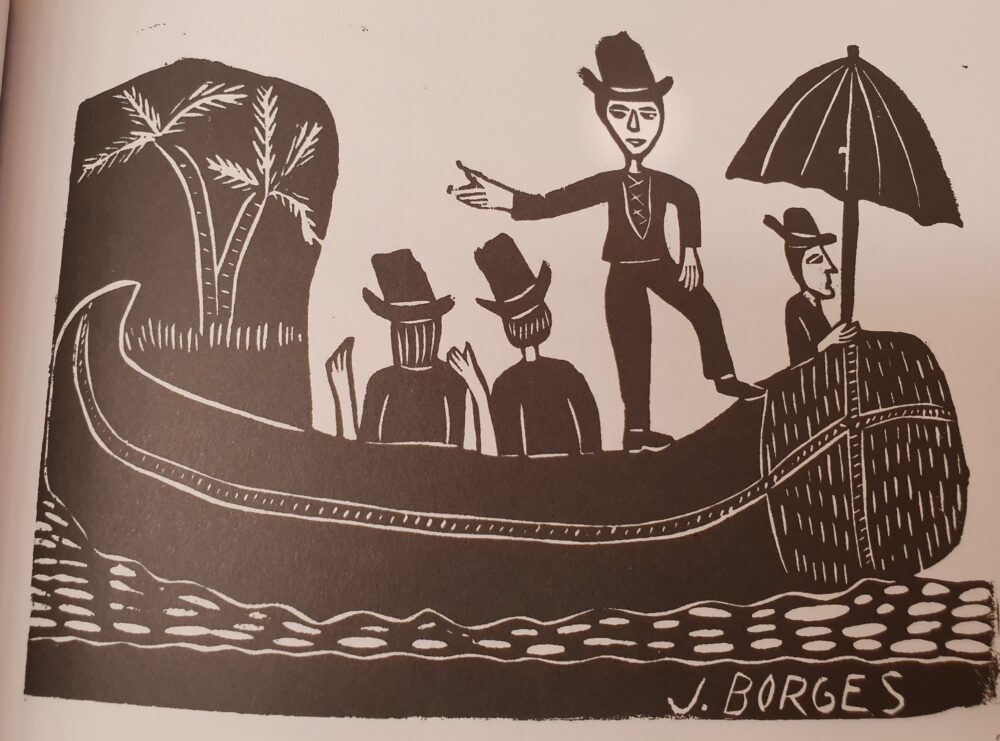

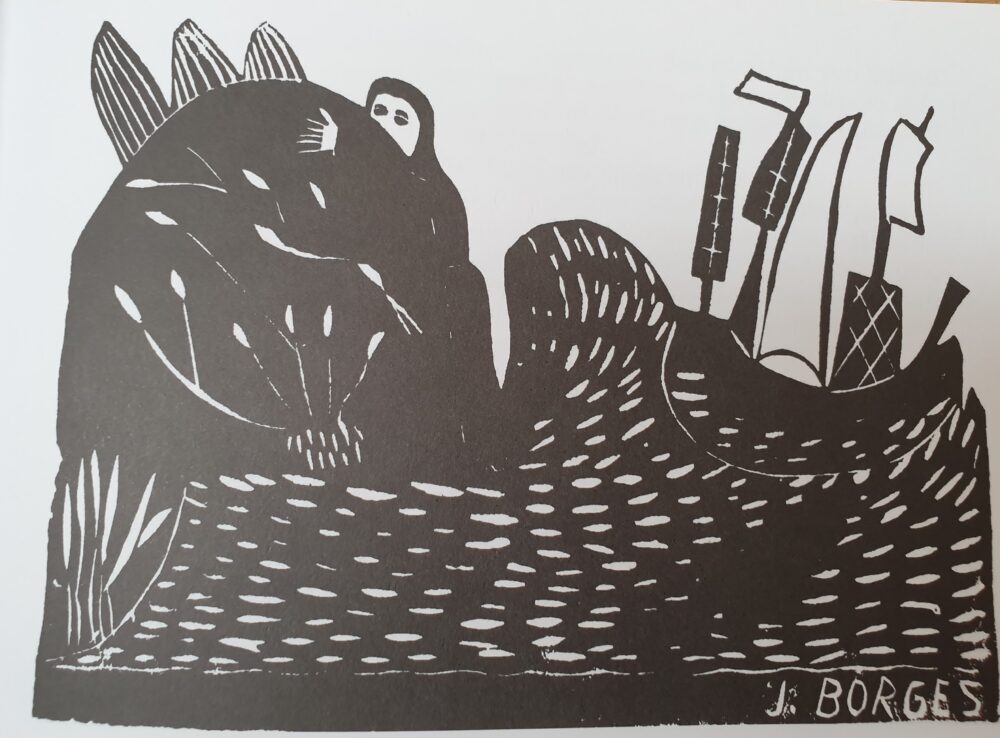

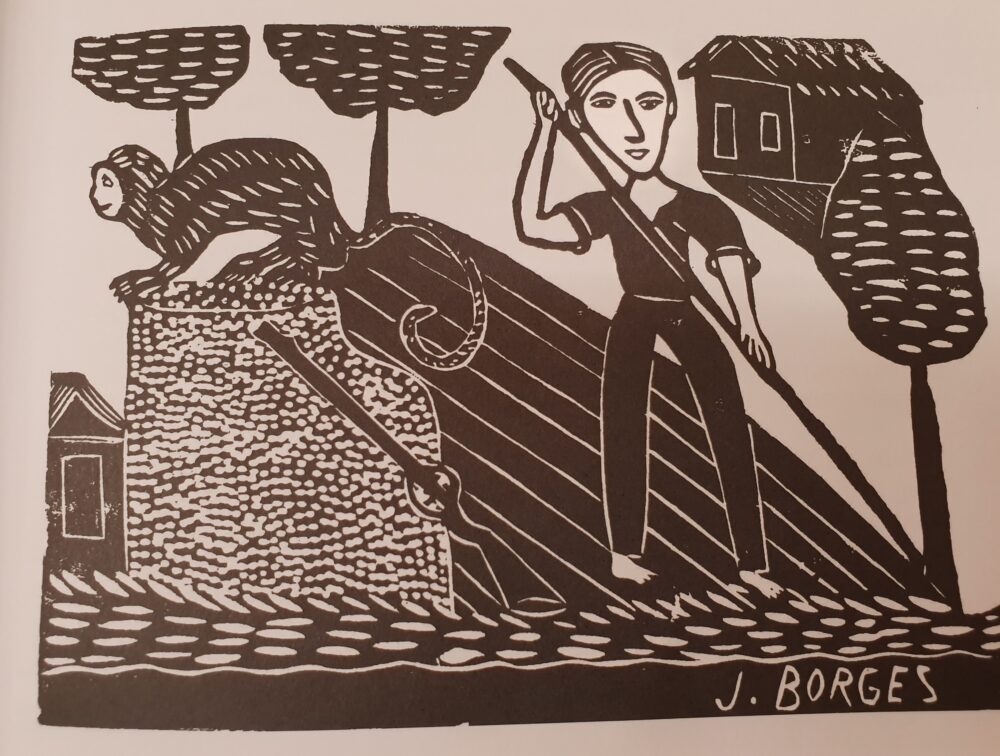

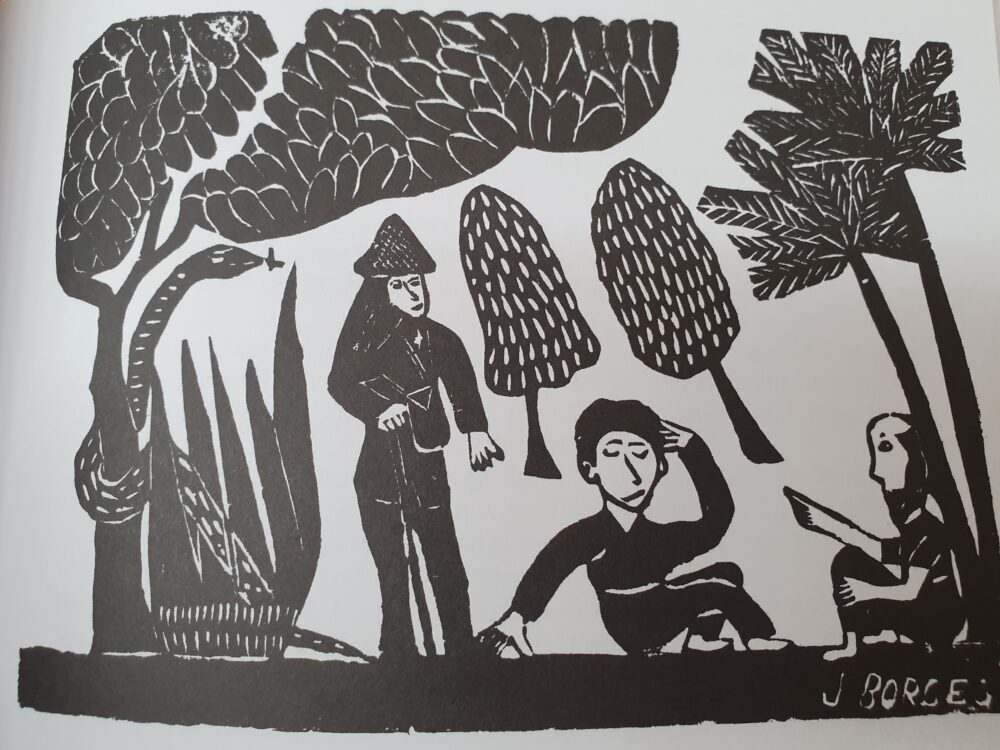

Amongst other works, the collection includes a set of woodcuts. Brazilian artist Jorge Borges was commissioned to provide a new approach to Robinson Crusoe and his seven woodcuts have been part of the Robinson-Library since 2001. Both the original woodcuts as well as the graphic prints they produced are on display – an interesting selection of scenes derived from Defoe’s novel, which itself has a highly graphic quality with its many realistic, detailed descriptions of life. Borges is an artist who works primarily with woodcuts.

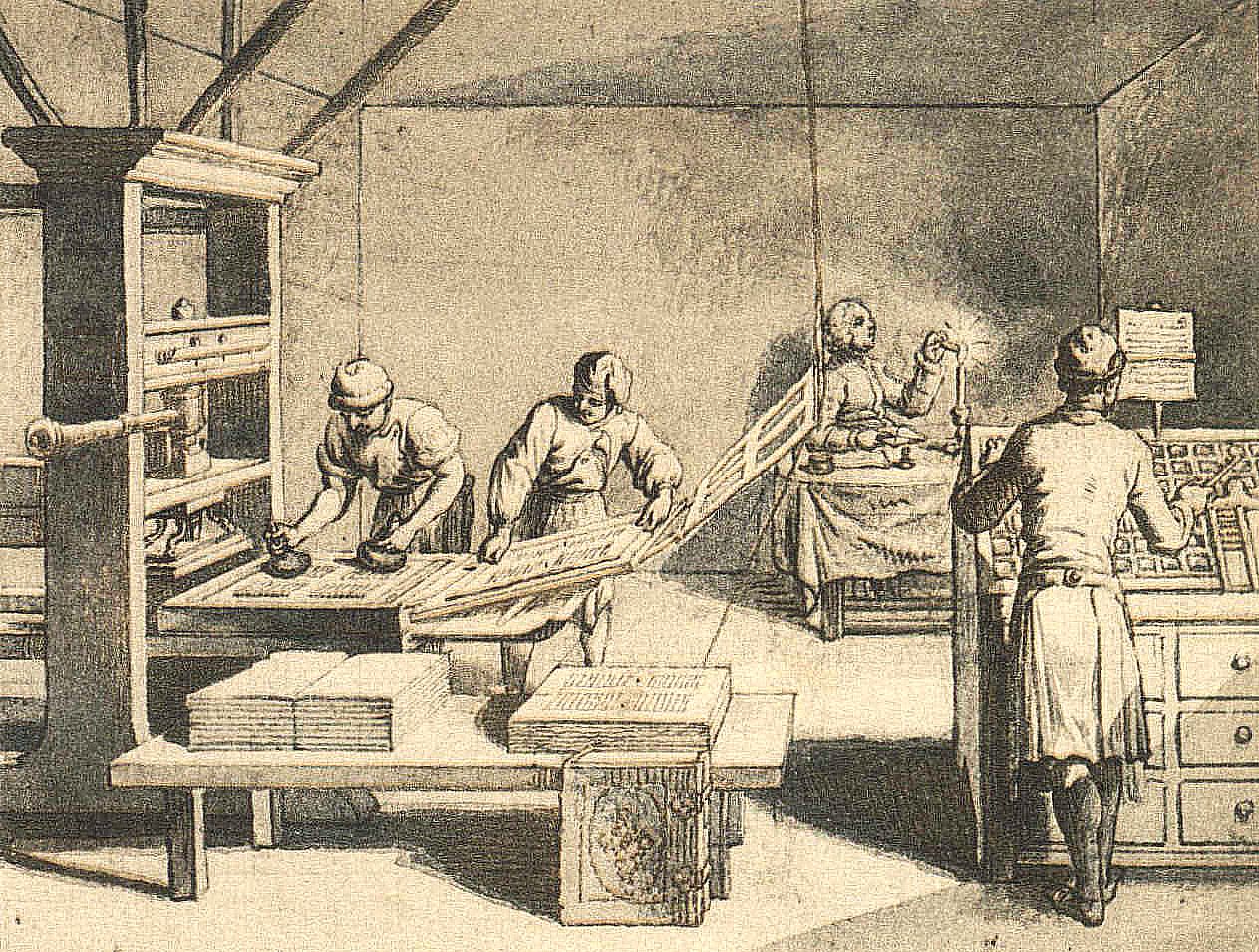

Making woodcut prints requires meticulous handcrafting and results in a 3D-relief negative, from which prints can be made. This medium shares a cultural history with Robinson Crusoe: the advent of the printing press centuries ago turned novels into a mass-medium, resulting in the spread and success also of Defoe’s novel – and Borges would not have been able to retell Robin Crusoe through his printed woodcuts, had it not been for this invention.

Borges’ woodcuts mimic the external transformation of Robinson Crusoe: they show a well-dressed, groomed and shaved individual evolve into the survivalist with long, unkempt hair and equipped with a big hat and rifle upon his encounter with Friday. What scenes are depicted and why? And what key moments from the novel are omitted? From “The Departure”, “On the Boat”, to “Shipwreck” and the succeeding “Arrival on the Island”, Borges includes a handful of scenes any fan of Robinson Crusoe may expect. Surprisingly, no woodcut depicts Crusoe’s arduous task of retrieving materials from the sinking ship or the famous footprint in the sand. Did Borges make these choices on technical grounds? Did his selection result in a specific aesthetic, drawing on his long-standing work as an artist? Is there another story to be told around these seven scenes?

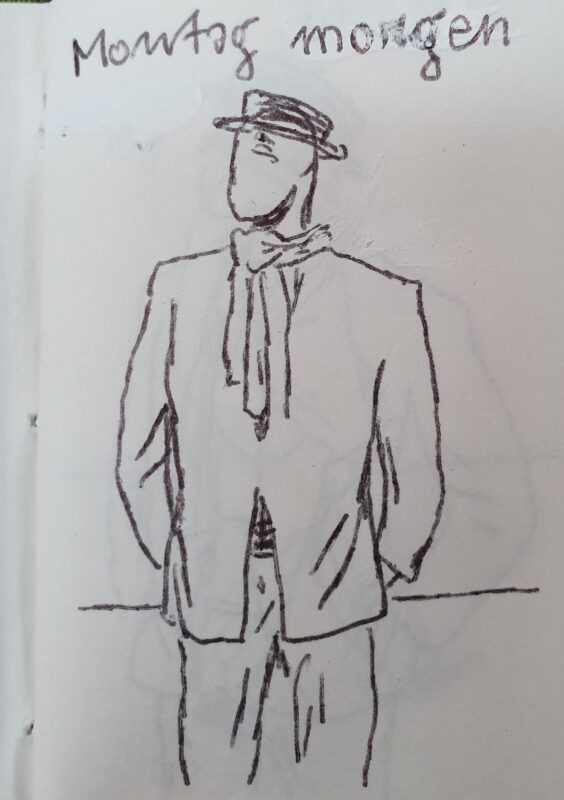

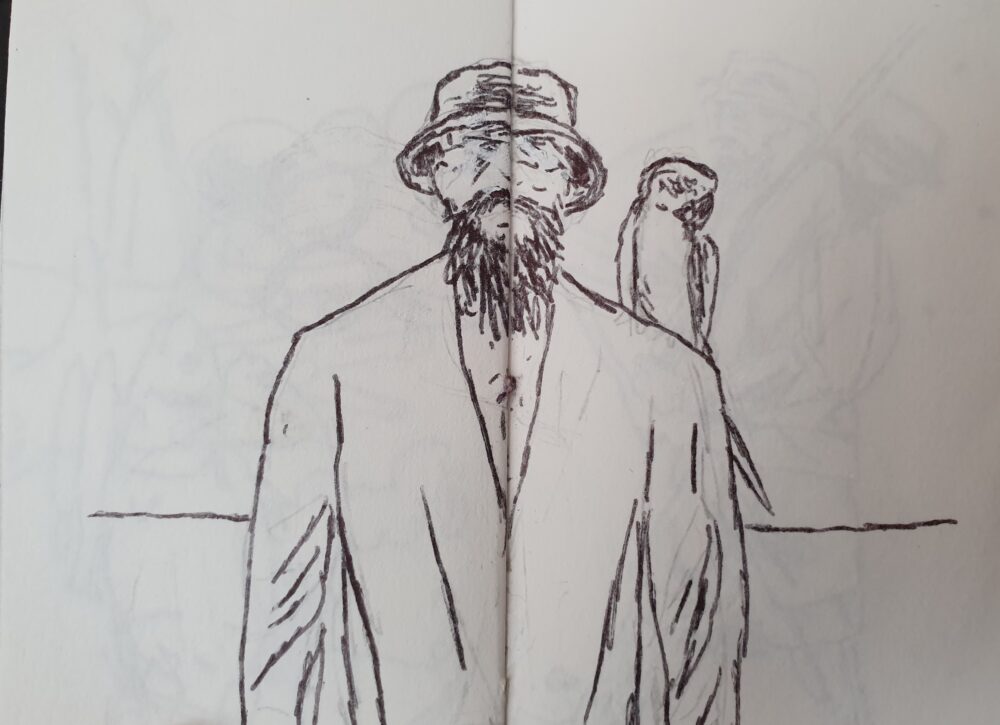

One object in the collection that does tell a different story about Robinson Crusoe is titled Monday Morning – Friday Evening. Difficult to find among the bigger tomes in the archive, this unique tiny book composed entirely of illustrations measures but 9.5 x 6.0 centimetres. It was created by Massimo Milano, an artist and illustrator originally from Italy, but based in Switzerland. This ant amongst giants does pack a punch, as interesting visual methods are used to give the famous story surprising twists. We see the well-dressed businessman Crusoe on Monday morning and follow him through his day, which transforms him – as in Borges’s series – into a long-bearded, hat-wearing vagrant with a parrot on his shoulder.

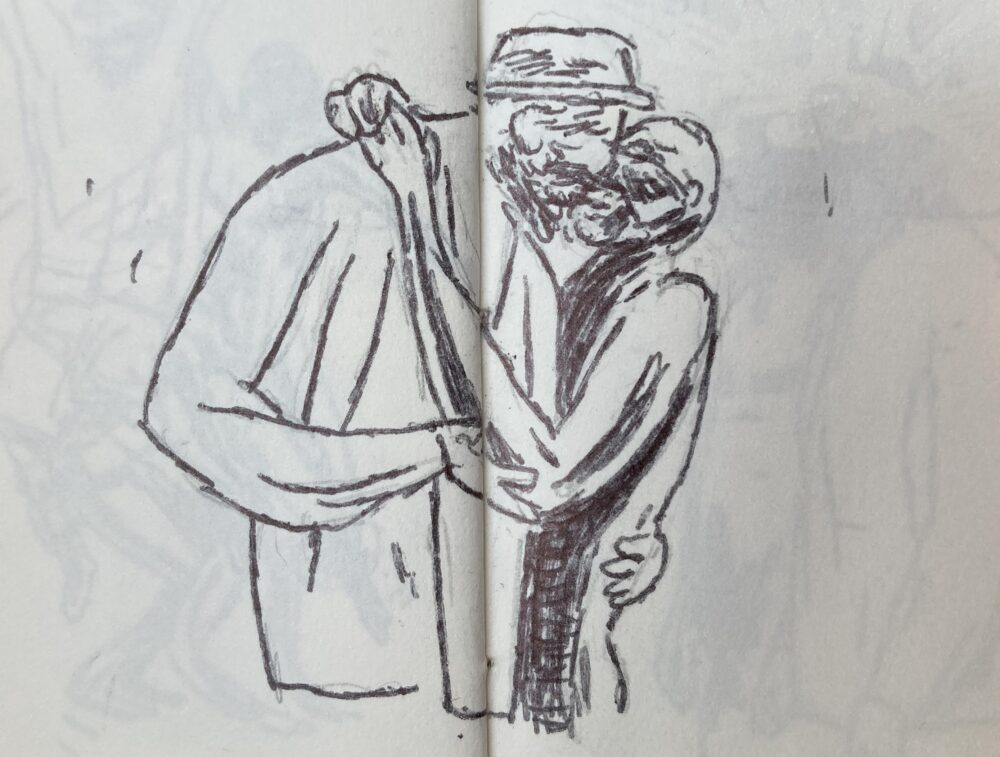

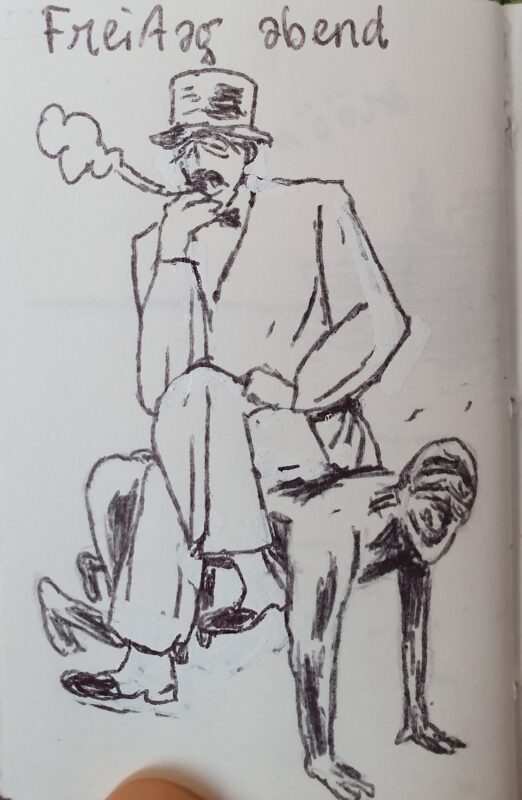

Two of Milano’s illustrations stand out in their irreconcilable contrast: one shows Crusoe and Friday in a passionate embrace; the other, final image shows Crusoe, dressed again in a smart suit, smoking a cigar and enjoying his ‘Friday evening’, while sitting on the back of Friday, who crouches on hands and knees. What has happened in the course of one week? What story of ‘civilized’ behaviour and passionate encounters between humans is being told here? Does the final image perhaps suggest that civilized behaviour is linked to the repression of one’s feelings, and the oppression of others?

Text: Yunus Durrer

Sources:

- Blewett, David. “The Iconic Crusoe: Illustrations and Images of Robinson Crusoe”. In The Cambridge Companion to ‘Robinson Crusoe’, ed. by John Richetti. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018, 159–19.

- Mueller, Andreas. “’To Us the Mere Name Is Enough’: Robinson Crusoe, Myth, and Iconicity”. In ‘Robinson Crusoe’ after 300 Years, ed. by Andreas Mueller and Glynis Ridley. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2021, 183–201.