Among the many books at the Robinson Library, some curious items of everyday life can be found that one would never expect on the shelves of a literary archive: a tin of tuna, a sheet of thin orange wrapping papers, a tray with single portions of coffee cream. A closer look reveals that they all bear scenes from Robinson Crusoe. Yet what does Defoe’s novel have to do with these mundane consumer goods?

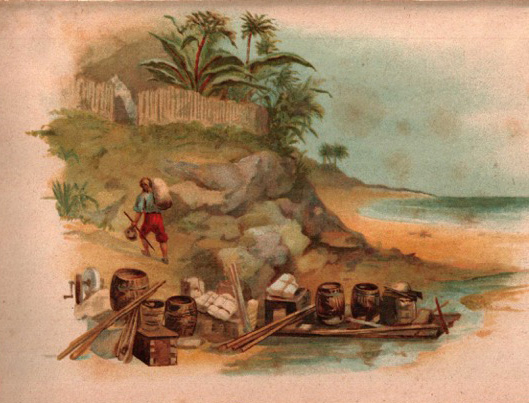

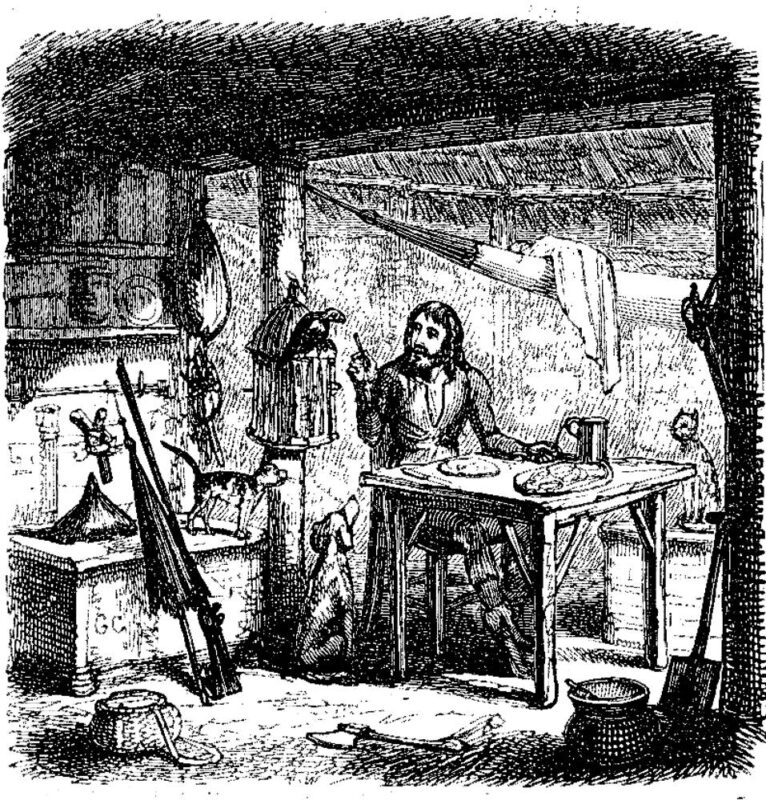

Stranded on his island, Robinson Crusoe himself is intensely preoccupied with procuring, storing and consuming material goods. His survival depends on being able to salvage as many items from the shipwreck as possible and to produce what he needs from scratch: tools, furniture, earthenware pots, clothes, as well as bread or beer. He considers their value not in money, but in how long they allow him to survive on the island. Pages upon pages of his diary – written with pen and paper also salvaged from the ship – list all the things he possesses and consumes. He also keeps lists to take stock of his dismal situation or when trying to make decisions where sheer necessity battles with conscience and faith, sounding very much like an accountant: “I stated very impartially,like debtor and creditor, the comforts I enjoyed against the miseries I suffered” (Robinson Cruose, 106). According to literary scholar Ian Watt, this accumulation of things and the habit of account-keeping for material as well as spiritual purposes, mark Crusoe out as homo economicus, the prototypical economic man (Watt 49).

In early eighteenth-century Britain, this economic man was becoming an example that a rising middle-class composed of tradesmen, shopkeepers, merchants and professional men tried to emulate. Great importance was given to industry, the dignity of labour, economic independence and individual freedom. God was thought to favour those who endorsed these virtues; wealth was seen as the rewards of a god-fearing life. Robinson embodies these virtues, even when battling with fears and doubts, and he returns home to England a rich man. That these riches stem from his plantation in Brazil, which was run on slave labour, troubles neither him nor, for all we know, Defoe’s first readers.

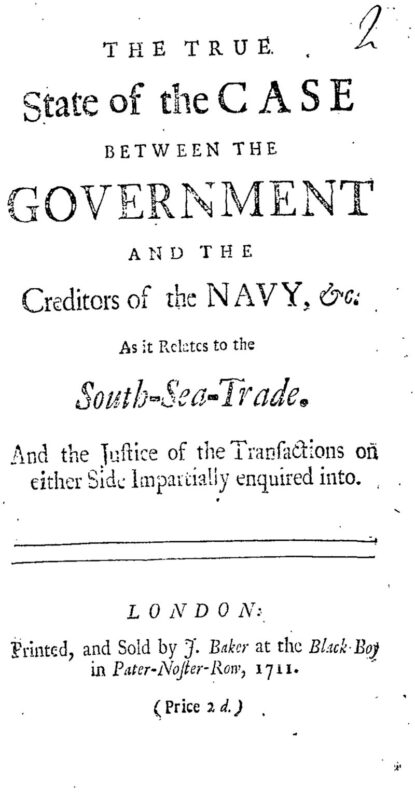

Daniel Defoe himself could also be seen as an economic man: originally a merchant importing goods from the continent, he later became an enterprising journalist who produced and sold his writings in the literary market. Before he wrote novels, Defoe published a great number of economic essays that considered domestic economics as well as international trading relations, often critically (Markley 306). His great success as an economic journalist reflects the popular interest in these topics: trade was considered not only a matter of professional pursuit or of national wealth, a but very much as something that affected everybody’s daily life. Importing many luxury goods from Europe, from Asia, and from the colonies in the new world, Britain was quickly becoming a consumer culture: wine, oil, spices, tobacco, sugar, tea, coffee, silk and other costly fabrics, pieces of furniture and porcelain from China, paintings, pieces of art and exotic birds alike were all bought and consumed in well-to-do British homes. Part of the allure of these consumer goods – then as now – was to demonstrate one’s economic success and social status.

But this thriving consumer culture energised by colonial trade also held the possibility of failure and ruin. Crusoe’s own shipwreck is a warning example in that the loss of ships and their load often spelled the bankruptcy of trading companies and the people who had invested in them. Investing in overseas trade had by then become a popular form of increasing one’s wealth, just like stock-market investments are for us today. And just as today, things could go horribly wrong: in 1720, just a year after Defoe had published his first novel and its sequel which sees Robinson embark on a voyage of trade to the Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific, the ‘South-Sea Bubble’ burst. Thousands of small shareholders as well as bigger investors who had bought stocks in the South Sea Trading Company in hope of profitable returns, which never materialized, faced the loss of all their money when the value of their shares plummeted by 80%. Was Crusoe’s island-existence seen as a salutary warning to remain content with the goods one can produce by one’s own hands? Was it a promise that one could survive even the most disastrous shipwreck? Or was the shipwreck rather a symbolic expression of some deep insecurity undercutting the faith in modern capitalism and consumer culture? (Markley 309)

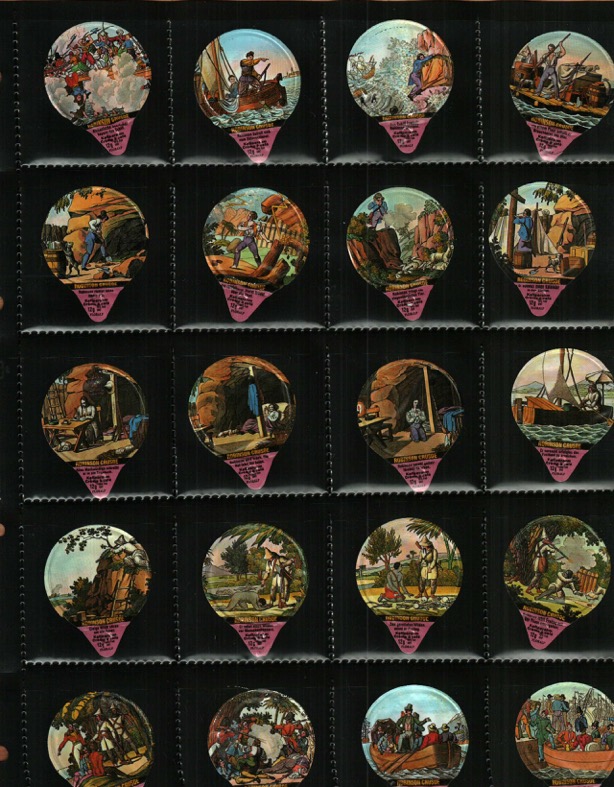

A can of tuna, or an orange, or a pod of coffee cream may not seem like the hight of luxury in our globalised world of delivery chains and constant availability. But the appeal of these exotic consumer goods is evoked by the name ‘Robinson Crusoe’ and scenes from the novel, which is maybe why they were chosen as advertisements in the first place. The thin paper wrappings are clearly meant to market the oranges in a manner that caters to children’s appetites: they are designed in a comic-book style and show easily recognisable scenes from Robinson’s life. One version depicts him sawing timber, catching a turtle, hunting goats, planting corn, or reading a book in the company of his sleeping dog. Another is less palatable: here, his violent encounters with the native ‘savages’ and Friday’s rescue from their hands are shown, with all natives depicted in a crudely reductive, cartoonish manner wearing straw skirts and bone-necklaces, having thick lips and curly hair. The novel never describes them in this way; what we see are the racist stereotypes still alive in the mid- to late twentieth century. The coffee-cream pods seem more measured and subtle, if only at first glance. The complete set of 20 pods tells the entire story of Robinson Crusoe, from his setting out to his return home. Four display him in the company of Man Friday, aways showing the native figure in a position of submission, servitude or inferior posture to a Crusoe who is clearly the master of every situation.

The tuna can is the least offensive item, likely because it does not deploy images, only the name ‘Robinson Crusoe’. This is the name of a food company established in 2010 and owned by the Spanish Jealsa group; it cans and distributes fish caught off the coasts of Brazil and Chile using, as the company website claims, only traditional, sustainable methods of fishing. The company’s slogan is “Life goes well with ROBINSON CRUSOE!” and it advertises some of its products as “Sourced from the pristine waters of Robinson Crusoe Island”. With its self-declared aim of combining sustainable fishing with environmental and social responsibilities, it seems set to countermand the negative images of colonial exploitation that have come to be associated with the name of Defoe’s hero by providing a positive vision for the future.

Text: Isabel Karremann

Sources:

- Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Vol. 1 of The Novels of Daniel Defoe. Ed. by W.R. Owens. New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Kwass, Michael. The Consumer Revolution, 1650-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Markley, Robert. “Economics”, in Daniel Defoe in Context, ed. by Albert J. Riviero and George Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023. 305-329.

- Owens, W. R. et al. The Political and Economic Writings of Daniel Defoe. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Watt, Ian. The Rise of the Novel 1957, London: Penguin Books, 1963.

- https://just2ce.eu/case-studies/case-study-jealsa-rianxeira-wesea/

The EU-funded research research-project JUST2CE currently examines the circular economy practices underpinning the company’s production processes and claims to sustainability. - https://robinsoncrusoe.com.br/en/home-english/

Company website with information on compliance directions and the ‘we sea’ campaign for social and environmental responsibility.