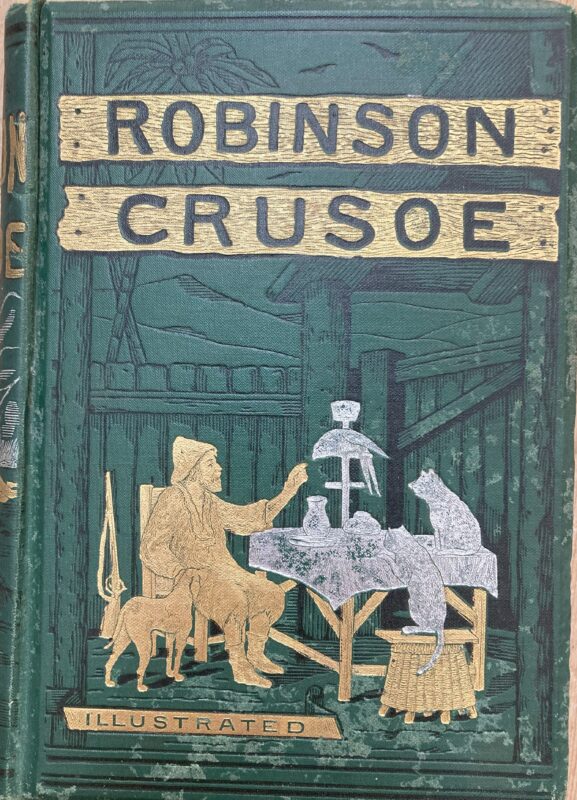

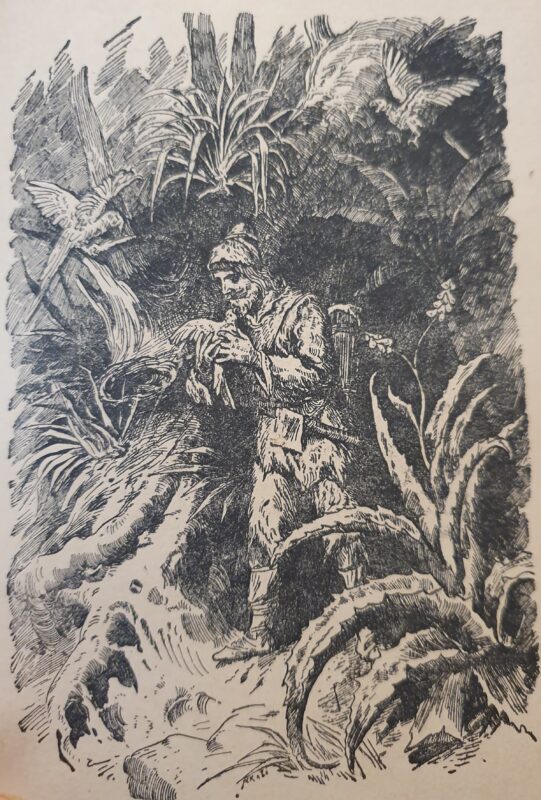

A common myth about Defoe’s novel is that Robinson Crusoe was alone on his island. What is often forgotten is that Robinson’s “little family” included his dog and the two cats. Beside domesticated pets, the island also hosts a wider range of familiar and of novel creatures that support or threaten Crusoe’s survival. These animals are ever-present throughout the story and, depicted on covers and in illustrations, are repeatedly brought to the readers’ attention in the many editions of Robinson Crusoe.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is often domesticated animals that appear in these illustrations, but also animal companions like the parrot that Crusoe “caught and taught [to] call him by his name” (Little Crusoe, 1841, p. 88). They are essential for his psychological wellbeing and ultimately his survival, whether as company or as food.

The one can segue into the other, as when Robinson cares for a kid with a broken leg and nurses it back to health: “I took such care of it that it lived, and the leg grew well and as strong as ever; but, by my nursing it so long, it grew tame, and fed upon the little green at my door, and would not go away. This was the First Time that I entertain’d a Thought of breeding up some tame creatures, that I might have Food when my Powder and Shot was all spent” (Robinson Crusoe, 113).

Arguably, animals also play the largest role in the smallest collection housed in the Robinson Library:

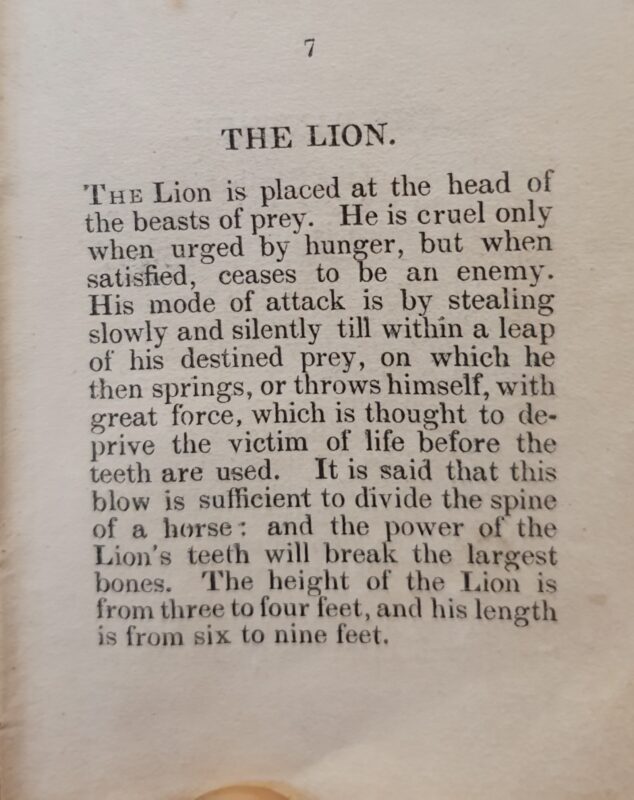

Little Robinson Crusoe (1841) is a miniature book, measuring only 7.5 by 6 cm, and can be found in a small cassette alongside an edition of Aesop’s fables and educational books on animals. Can you imagine a British child reading about Robinson’s encounter with a lion, and turning to their Little Book of Foreign Animals (1840) to read the description of the beast? Here, animals are used to entertain and educate young readers.

“Whilst they were prowling about on this wild shore, they came unexpectedly on a most terrific sight indeed – it was a very great lion fast asleep! Happily, Robinson had his gun with him, with which he shot the lion. They then went up to him, took off his skin, and with this returned again to their boat.”

(Little Robinson Crusoe, p. 31)

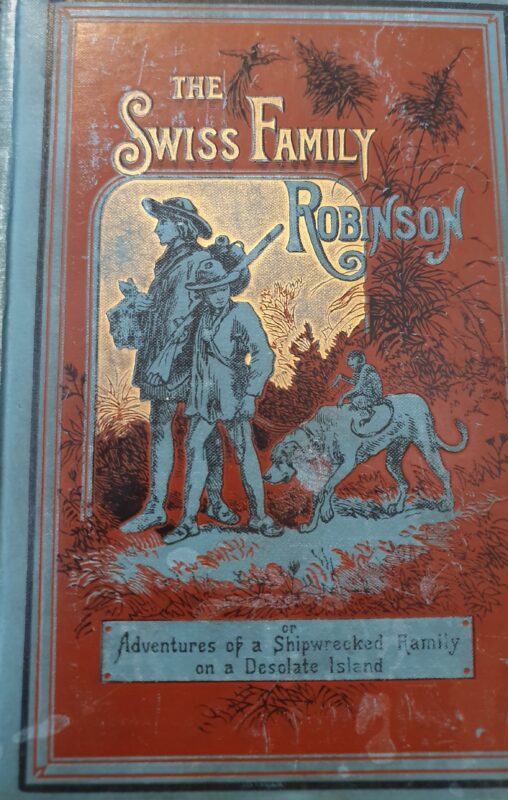

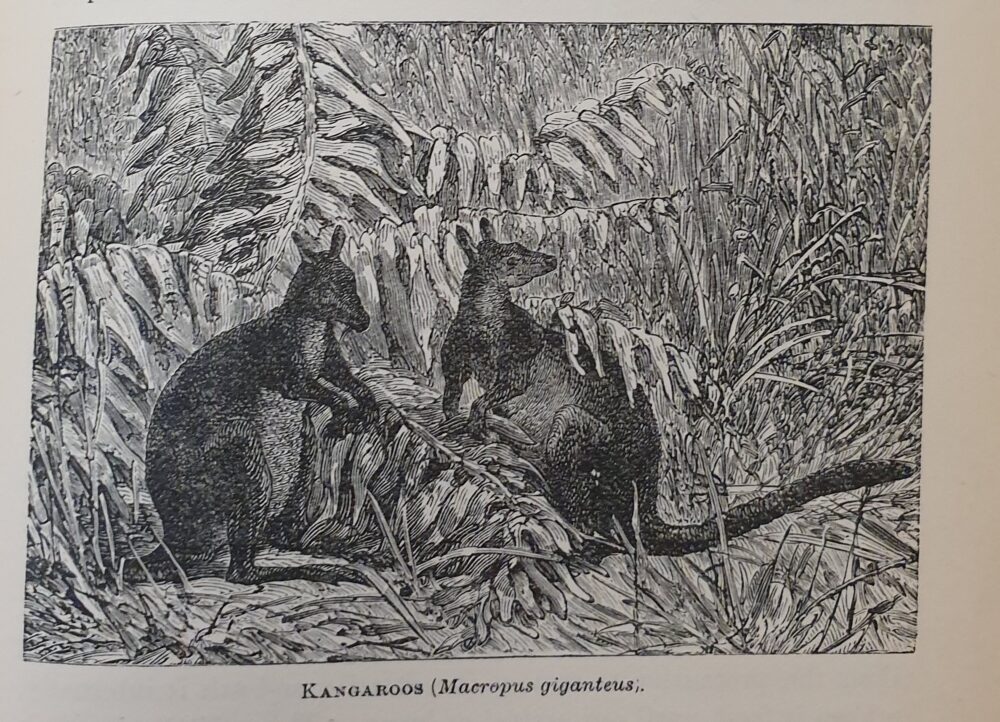

Illustrations of less familiar animals also feature in many adaptations of Robinson Crusoe. In an edition of The Swiss Family Robinson from 1902, for example, the family classify the animals on the island but struggle with identifying a kangaroo, whose appearance reminds them of other species. Only by recalling the voyage narrative of the famous British explorer Captain James Cook can they situate what they see in a familiar frame of reference and thus identify the animal. The adaptation plays with strangeness and familiarity as didactic tools to introduce zoology. Similarly, Joachim Heinrich Campe’s eighteenth-century Robinsonade Robinson the Younger (German original 1779, Robinson der Jüngere; English translation 1855) also aimed to educate its young readers, replacing goats with llamas. In foregrounding unfamiliar animals, these editions echo Crusoe’s experiences with encountering and domesticating the ‘exotic’ animals of an unfamiliar island.

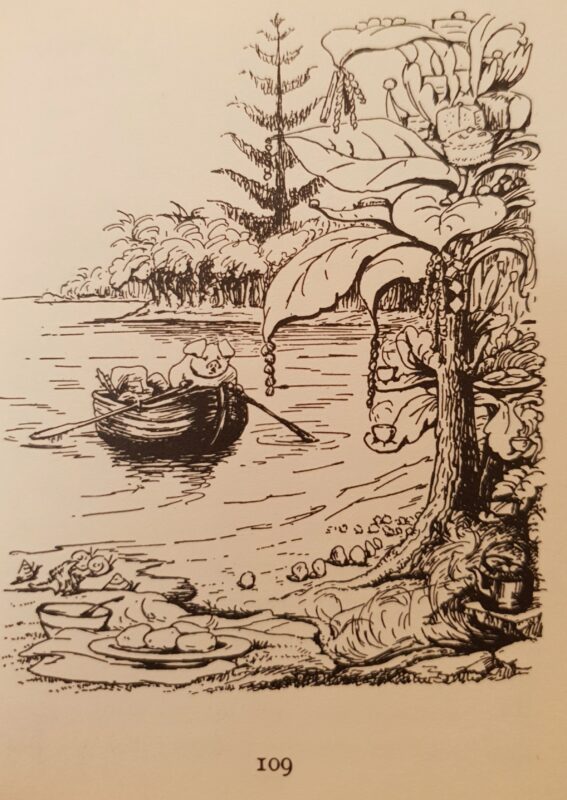

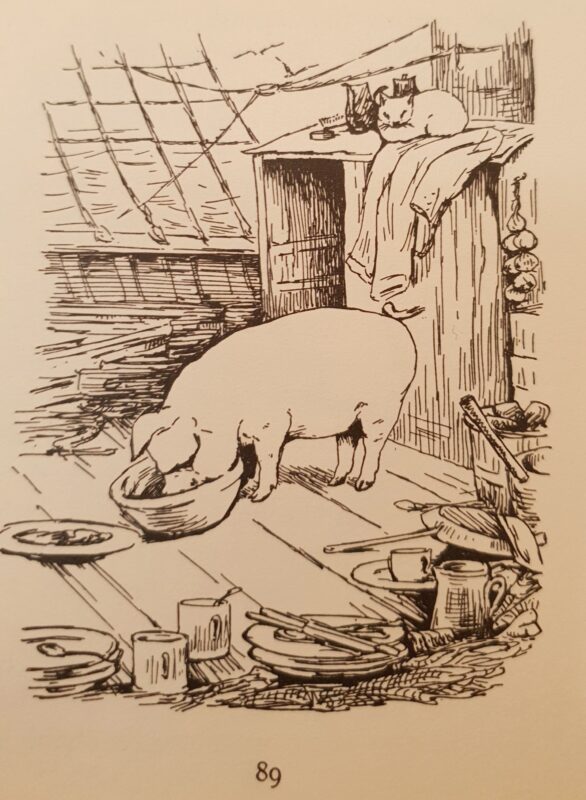

Throughout these adaptations, animals take on roles not initially included in Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, or sometimes even replace its characters. In Beatrix Potter’s children’s book, The Tale of Little Pig Robinson (1930), for instance, the protagonist is a pig. On the way to the market, Little Pig Robinson is kidnapped by a ship’s cook, who tricks the naïve piglet into sailing to sea. On board, Robinson is fattened and threatens to end up in a cooking pot — but it manages to escape just in time with a boat, landing on a paradisiac island, which is “very like Crusoe’s, only without its drawbacks” (111).

The tale is inspired by Edward Lear’s poem The Owl and the Pussy-cat (1871), in which an owl and a cat travel to an island and meet a pig. While the story of the pig emerges directly from Lear’s poem, Potter had to change aspects of her other source, Defoe’s novel, to suit the animal’s anthropomorphic character. While Crusoe is self-sufficient and driven, the pig is dependent and needy, struggling to survive on its own. Potter’s story thus exploits the tension between the anthropomorphic and creaturely aspects of the animal characters, especially in her illustrations. In some, the animals behave like humans, while in others they are naked, voiceless, and walk on all fours.

This contrast produces a humorous and sometimes even challenging undertone that questions on the cohabitation of animals and humans, as well as the consumption of meat. Of course, if you would like to learn more about Little Pig Crusoe’s adventures and these illustrations, you will have to visit him in the archive…

Text: Olivia Conroy

Sources:

- Campe, Joachim Heinrich. Robinson Der Jüngere. Konstanz: Buch- und Kunstverlag Carl Hirsch, A.G., 1925.

- Child, Isabella, W. May, and C. Williams. The Little Robinson Crusoe; The Little Esop. London: Tilt & Bogue, 1841.

- Potter, Beatrix. The Tale of Little Pig Robinson. London: F. Warne & Co., 1930.

- Wyss, Johann David, and Johann Rudolf Wyss. The Swiss Family Robinson. London: Nelson, 1902.