When a novel is so popular as Robinson Crusoe, it is perhaps natural that its figures will also appear in other media – like games and toys. These started appearing on the market during the 19th century and have not stopped since. The Robinson-Library contains a colourful selection of such playthings, including quartets, board games, cube puzzles and pop-up books.

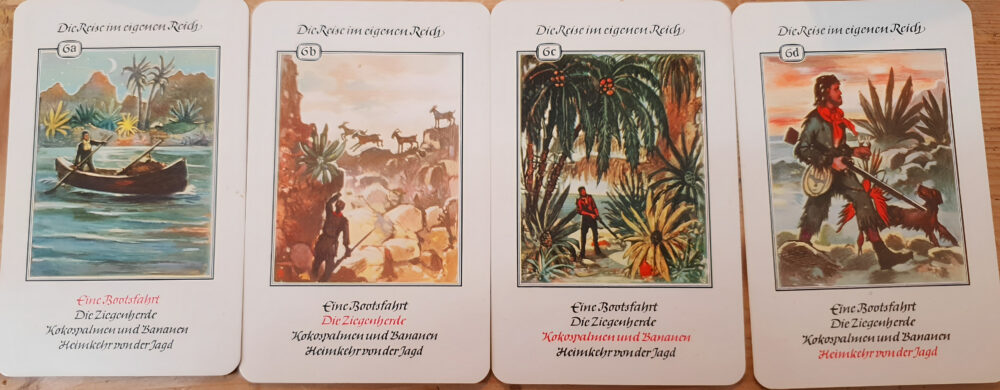

But what does such a shift in medium mean for the story? Obviously, a game is a different object than a novel: other rules apply and the possibilities of representing the story are different. Take the quartet set produced in Germany around 1960, for example. There are 36 cards that contain images on one side and retell Crusoe’s story on the other. They are divided into groups of four, each focusing on one aspect of the story, such as “Travels in His Realm” or “The First Days on the Island”. This episodic grouping breaks up the storyline, simplifies the narrative and thus makes it easier to grasp.

There are further differences between the novel and the set. While Defoe’s original story elaborately describes Crusoe’s ponderings and contemplations, the quartet set focuses on events and action. A multilingual board game from the mid-19th century highlights this distinction even more.

It contains no text but only images depicting different parts of Crusoe’s story. By rolling the dice, you try to be the quickest to reach the inner field of the spiral. Actively traversing the fields allows the player to re-enact Crusoe’s adventures and experience them first-hand. As if to account for the unpredictability of life and the random inconveniences Crusoe faces, the game’s rules confront you with some rather bizarre twists. They make the game hilariously complicated. Just imagine having to remember all these rules (among many more) while playing:

“If you land on Robinson, the hero of the game, meaning on numbers 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 17, etc., you get to move forward again as much as you already moved; but if you land on a ship, i.e., numbers 2, 5, 27, you have to return to the slot on which you started your turn. Whoever throws a 6 on the first roll receives 4 tokens from the bank. On number 13, one has to pay 8 tokens, but on number 15, one receives 12 tokens. Should a player land on the beach number 7, they remain there until another player rescues them, meaning, until then, they cannot play.”

If, among the turbulences of family board-game night, you find a moment to look at the images, you can spot a focus on nature: flowers, bushes, goats, birds. This emphasis on the natural world is also present in the cube puzzle (year unknown), whose sides show different pictures of Crusoe on the island. Each depicts idyllic scenes from nature.

The colours are warm and bright, the ocean is a soft blue, and the plants are luscious and vibrant. Thus, the game evokes in the viewer a nostalgic feeling of a simpler past. This was done quite intentionally: by tapping into nostalgia, the game’s creators aimed to appeal to an adult audience, who were thereby animated to purchase the product. When looking at the toy’s condition, it appears that this strategy has worked well: the edges of the cubes look worn from playing, and the template papers appear heavily consulted. In short, the game seems to have been dearly beloved and often played with.

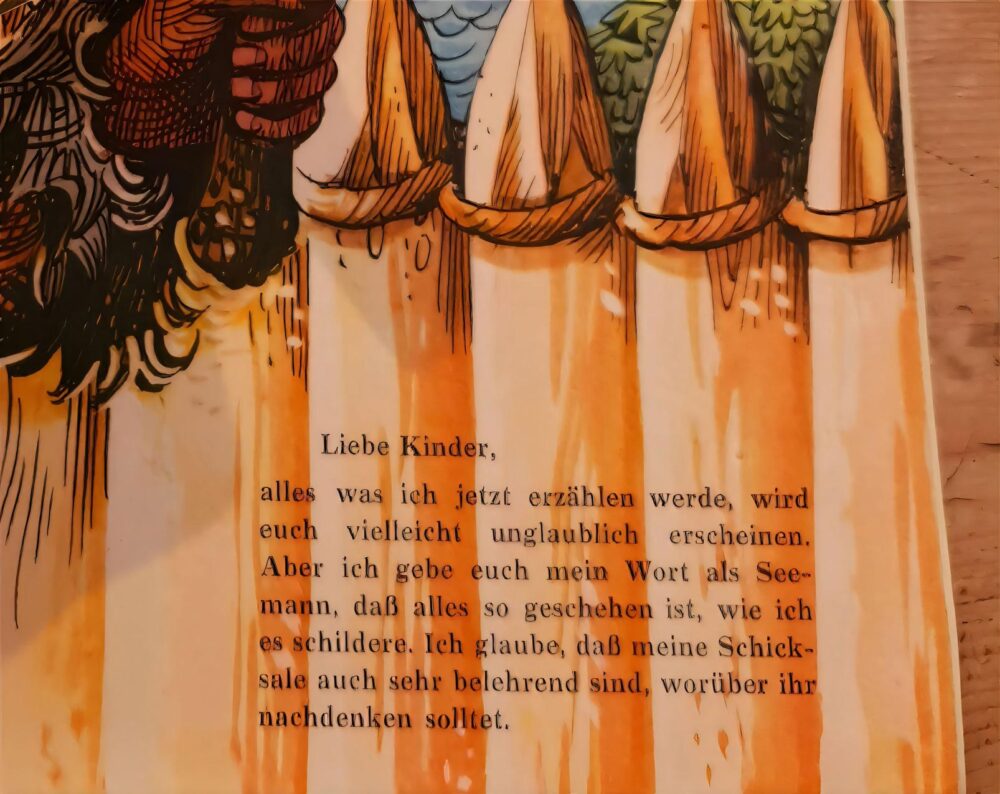

The playthings were also crafted to make parents want to buy them for their children. One such strategy was to assure the mothers and fathers that the game had a didactic value. Look at the preface of this pop-up book from 1957.

The book then tells the story of Robinson Crusoe in a simplified way, continually interjecting short statements of wisdom, such as: “While the storm wind roared and the rain slipped through the wooden panels of my hiding place, I became convinced that it would be necessary to create a more solid dwelling that would defy the storms and the downpours with their dire consequences. As so often before, I realized that superficial and negligent work is not worthwhile, that it works against me, and that only through well thought-out and carefully executed work I will be able to preserve my life and health.”

The simplified narrative excludes or adjusts scenes that are more complex or involve problematic subjects such as slavery. Through this, the parents don’t have to go on a philosophical tangent with their ten-year-old right before bedtime. The pop-up book also features a 3D-representation of Crusoe’s home. It invites the children (and adults) to discover and play. In this way, the toy opens a whole new realm of storytelling. It taps into our creativity, and the words move beyond the text. Through playing with Robinson, children and adults are allowed to add to the story and let it come to life in a whole new way.

Text: Jana-Maria Humbel

Sources:

- Buijnsters, Piet J., and Leontine Buijnsters-Smets. Papertoys: Speelprenten en Papieren Speelgoed in Nederland (1640–1920). Waanders, 2005.

- O’Malley, Andrew. Children’s Literature, Popular Culture, and Robinson Crusoe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.