Who has not, as a child, spent days building a fort in a remote corner of a garden or maybe even in the nearby woods, pretending to be cast away on a desert island and having to survive all on one’s own? It was surely such a childhood fantasy that inspired a little booklet from 1955, called Like Robinson in a Tent, which introduces children to the skills of camping out. It uses the Robinson story as an opportunity to provide information about camping: it gives useful tips, tells personal anecdotes, and shows in illustrations how to build a tent or a fire.

As an example of literature for children and young adults – a genre to whose development rewritings of Robinson Crusoe have contributed substantially – this booklet is both entertaining and educational. The story follows the usual pattern: the protagonists leave the safety of home to encounter a variety of challenging adventures before finally returning home again, being more mature than before (see O’Malley, 93–94). Interestingly, this book for young children starts in a rather literary way: it begins by introducing its readers to a (only partly correct) publication history of Daniel Defoe’s classic and portrays the character of Robinson Crusoe as a role model whose life in nature is much preferable to living in the industrialized city. In a simplified manner, the book thus endorses the motto ‘back to nature’ which the French Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau first identified as the novel’s core message.

The booklet’s vision of living in harmony with nature includes references to the life of nomadic peoples. These references are sometimes problematic where such peoples’ cultures are compared to simpler, even pre-civilizatory ways of life. By contrast, the booklet creates a sense of easy familiarity for its (Swiss) readers through a language that seems inclusive but silently creates exclusions: it always says ‘first we build a tent’ and talks about ‘our camping ground’, without mentioning that these practices and skills have been learned from nomadic civilizations. This emphasis on creating a strong sense of Swiss identity and outdoor culture aligns with then strongly patriotic philosophy of the publishing company, the Schweizerisches Jugendschriftwerk.

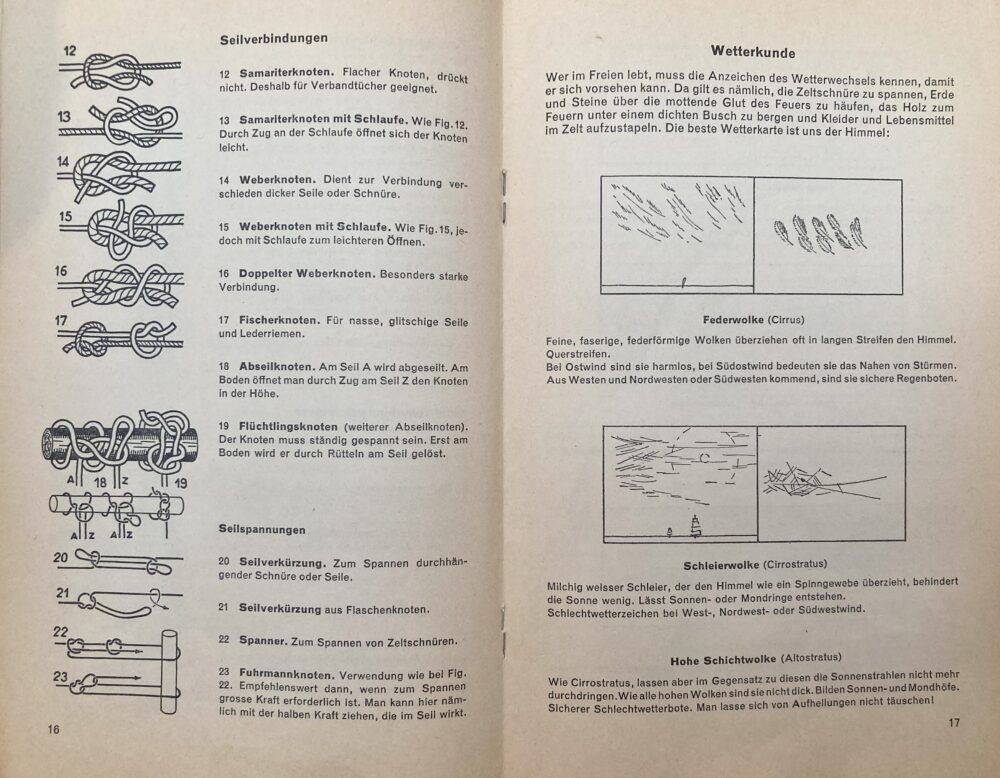

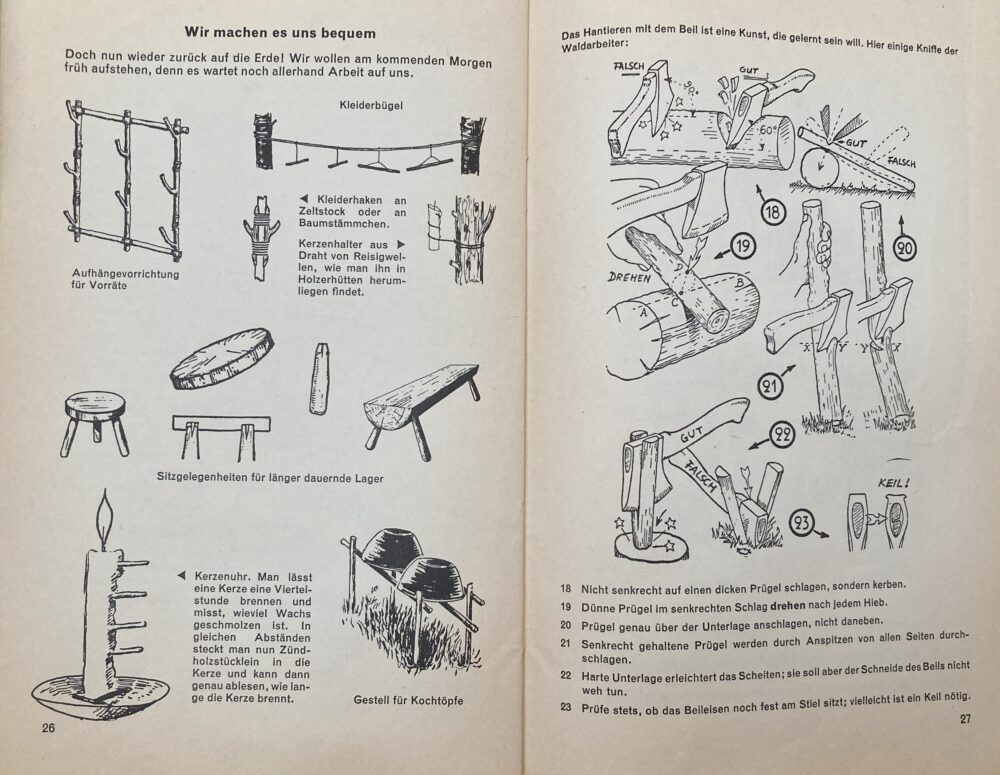

While Robinson Crusoe inspired the title and the theme of the book, most of the content revolves around directions and instructions on how to find a suitable place for camping, how to set up a tent, interpret clouds for changes in weather, and much more. These instructions are accompanied by illustrations, just like in a manual, to clarify and visualise what is explained in the text. Sometimes the black and white drawings also embellish the little nostalgic insertions by the narrator. His hands-on advice along with the romanticising personal anecdotes about camping carefully whet one’s appetite to go on such an adventure as well.

On the whole, When Robinson in a Tent provides a varied account of all the things to which one should pay attention when camping in, and thus when being part of, the great outdoors. Robinson Crusoe himself surely would have been grateful to have found a copy of this book, along with the Bible, on his visits to the shipwreck – and he would also have had few troubles accepting the colonialist stereotypes one still encounters in a children’s book from 1955.

Text: Naomi Wolter

Sources:

- Knobel, Bruno. Als Robinson im Zelt (Nr. 518). Illustrated by Gunther Schärer. Zürich: Schweizerisches Jugendschriftenwerk, 1955.

- O’Malley, Andrew. “Crusoe’s Children: Robinson Crusoe and the Culture of Childhood in the Eighteenth Century.” In The Child in British Literature, ed. by Adrienne E. Gavin. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 87–100.